It takes a long time to grow a debt bubble, but history shows that in reality it is not that long. 80 years on average, a human lifespan. If you take the early 1950s as the start of the current one, we are almost there, close to the end of the current one. What will give first? Debt in China? Profligacy in the US? Distortions in Europe? This article explains this last possibility. I agree. This would explain the Covid madness engulfing the continent...

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

A Euro Catastrophe Could Collapse It

This article looks at the situation in the euro system in the context of rising interest rates. Central

to the problem is role of the ECB, which through monetary inflation

embarked on a policy of transferring wealth from fiscally responsible

member states to the spendthrift PIGS and France. The consequences of these policies are that the spendthrifts are now ensnared in irreversible debt traps.

Even

in a Keynesian context, the ECB’s monetary policy is no longer to

stimulate the economy but to keep the spendthrifts afloat. The

situation has deteriorated so that Eurozone commercial banks appear to

have credit restricted in New York, evidenced by the reluctance of the

US banks to enter into repo transactions with them, leading to the

market failure in September 2019 when the Fed had to intervene.

An examination of the numbers strongly suggests that even Eurozone banks, insurance companies and pension funds are no longer net buyers of Eurozone government debt.

It could be because the terms are unattractive. But if that is the case

it is an indictment of the ECB’s asset purchase programmes deliberately

suppressing rates to the point where they are unattractive, even to

normally compliant investors.

Consequently, without any savings offsets, the ECB has gone full Rudolf Havenstein,

and is following similar inflationary policies to those that

impoverished Germany’s middle classes and starved its labourers and the

elderly in 1920-1923. That the German people are tolerating such an

obvious destruction of their currency for the third time in a hundred

years is simply astounding.

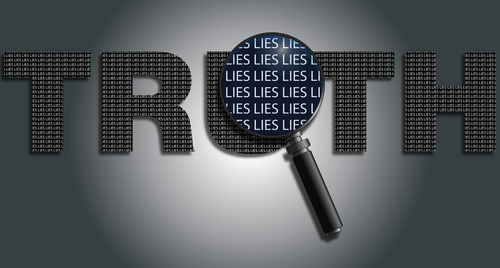

Institutionalised Madoff

Schemes

to pilfer from people without their knowledge always end in disaster

for the perpetrators. Central banks using their currency seigniorage are

no exception. But instead of covering it up like an institutionalised

Madoff they use questionable science to justify their openly fraudulent

behaviour. The paradox of thrift is such an example, where penalising

savers by suppressing interest rates supposedly for the wider economic

benefit conveniently ignores the theft involved. If you can change the

way people perceive reality, you can get away with an awful lot.

The

mass discovery by the people of the fraud perpetrated on the people by

those supposedly representing the people is always the reason behind a

cycle of crises and wars. It can take a long period of suffering before

an otherwise supine population refuses to continue submitting

unquestionably to authority. But the longer the condition exists, the

more oppressive the methods that the state uses to defer the inevitable

crisis become. Until something finally gives. In the case of the euro,

we have seen the system give savers no interest since 2012, while the

quantity of money and credit in circulation has debased it by 63%

(measured by M3 euro money supply).

Furthermore, prices can be

rigged to create an illusion of price stability. The US Fed increased

its buying of inflation-linked Treasury bonds (TIPS) since March 2020 at

a faster pace than they were issued by the US Treasury, artificially

pushing TIPS prices up and creating an illusion that the market is

unconcerned about price inflation.

But that is not all. Government

statisticians are not above fiddling the figures or presenting figures

out of context. We believe the CPI inflation figures are a true

reflection of the cost of living, despite the changes over time in the

way prices are input. We believe that GDP is economic growth — a

questionable concept — and not growth in the quantity of money. We even

believe that monetary inflation has nothing to do with prices.

Statistics are designed to deceive. As Lord Canning said 200 years ago,

“I can prove anything with statistics but the truth”. And that was

before computers, which have facilitated an explosion in the quantity of

questionable statistics. Can’t work something out? Just look at the

stats.

A further difference between Madoff and the state is that

the state forces everyone to submit to its monetary frauds by law. And

since as law-abiding citizens we respect the law, we even despise those

with the temerity to question it. But in the process, we hand enormous

power to the monetary authorities, so should not be surprised when that

power is abused, as is the case with interest rates and the dilution of

the state’s currency. And it follows that the deeper the currency fraud,

when something gives, the greater is the ensuing crisis.

The best

measure of market distortions from deliberate actions of the monetary

authorities we have is the difference between actual bond yields and an

estimate of what they should be. In other words, assessments of the

height of negative real yields. But any such assessment is inherently

subjective, with markets and statistics either distorted, rigged, or

unable to provide the relevant yardstick. But it makes sense to assume

that the price impact, that is the adjustment to bond prices as markets

normalise, is greatest for those where nominal bond yields are negative.

This means our focus should be directed accordingly. And the major

jurisdictions where this applies is Japan and the Eurozone.

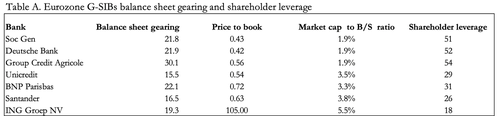

The eurozone’s banking instability

A

critique of Japan’s monetary policy must be reserved for a later date,

in order to concentrate on monetary and economic conditions in the

Eurozone. The ECB first reduced its deposit rate to 0% in July 2012.

That was followed by its initial introduction of negative deposit rates

of -0.1% in June 2014, followed by -0.2% later that year, -0.3% in 2014,

-0.4% in 2016 and finally -0.5% in September 2019. The last move

coincided with the repo market blow-up in New York, the day that the

transfer of Deutsche Bank’s prime dealership to the Paris based BNP was

completed.

We can assume with reasonable certainty that the

coincidence of these events showed a reluctance of major US banks to

take on either of these banks as repo counterparties, as hedge and money

funds with accounts at Deutsche decided to move their accounts

elsewhere, which would have blown substantial holes in Deutsche’s and

possibly BNP’s balance sheets as well, thereby requiring repo cover. The

reluctance of American banks to get involved would have been a strong

signal of their reluctance to increasing their counterparty exposure to

Eurozone banks.

We cannot know this for sure, but it is the

logical explanation for what happened. In which case, the repo crisis in

New York was an important advance warning of the fragility of the

Eurozone’s monetary and banking system. A look at the condition of the

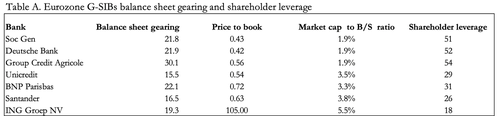

major Eurozone global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) in Table A,

explains why.

Balance

sheet gearing for these banks is roughly double that of the major US

banks, and except for Ing Group, deep price-to-book discounts indicate a

market assessment of these banks’ credit risk as exceptionally high.

Other Eurozone banks with international counterparty business deemed not

significant enough to be labelled as G-SIBs but still capable of

transmitting systemic risk could be even more highly geared. The reasons

for US banks to limit their exposure to the Eurozone banking system on

these grounds alone are compelling. And the persistence of price

inflation today is a subsequent development, likely to expose these

banks as being riskier still because of higher interest rates on their

exposure to Eurozone government and commercial bonds, and defaulting

borrowers.

The euro credit cycle has been suspended

When

banks buy government paper, it is usually because they see it as the

risk-free alternative to expanding credit to non-financial private

sector actors. In the normal course of an economic cycle, it is

inherently cyclical. Both Basel and national regulations enhance the

concept that government debt is risk-free, giving it a safe-haven status

in times of heightened risk. In a normal bank credit cycle, banks will

tend to hold government bills and bonds with less than one year’s

maturity and depending on the yield curve will venture out along the

curve to five years at most.

These positions are subsequently

wound down when the banks become more confident of lending conditions to

non-financial borrowers when the economy improves. But when economic

conditions become stagnant and the credit cycle is suspended due to lack

of recovery, banks can accumulate positions with longer maturities.

Other

than the lack of alternative uses of bank credit, this is for a variety

of reasons. Trading desks increasingly seek the greater price

volatility in longer maturities, central banks encourage increased

commercial bank participation in government bond markets, and yield

curve permitting, generally longer maturities offer better yields. The

more time that elapses between investing in government paper and

favouring credit expansion in favour of private sector borrowers, the

greater this mission creep becomes.

As we have seen above, the ECB

introduced zero deposit rates nearly 10 years ago, and private sector

conditions have not generated much in the way of bank credit funding.

Lending from all sources including securitisations and bank credit to a)

households and b) non-financial corporations since 2008 are shown in

Figure 1.

Before

the Covid pandemic, total lending to households had declined from $9

trillion equivalent in 2008 to $7.4 trillion in 2019 Q4. And for

non-financial corporations, total lending declined marginally over the

same period as well. Admittedly, this period included a credit slump and

recovery, but on a net basis lending conditions stagnated.

But

bank credit for these two sectors will have contracted, allowing for net

bond issuance of collateralised consumer debt and by corporations

securing cheap finance by issuing corporate bonds at near zero interest

rates, which are contained in Figure 1.

Following the start of the

pandemic, lending conditions expanded under government direction and

borrowing by both sectors increased substantially.

Meanwhile, over

the same period bond issuance to governments increased, particularly

since the pandemic started, illustrated in Figure 2.

The

charts in Figures 1 and 2 support the thesis that credit expansion and

bond finance had, until recently, disadvantaged the non-financial

private sector. The expansion of government borrowing has been entirely

through bonds bought by the ECB, as will be demonstrated when we look at

the euro system balance sheet. They confirm that zero and negative

rates have not stimulated the Eurozone’s economies as Keynesians

theorised. And the increased credit during the pandemic reflects

financial support and not a renewed attempt at Keynesian stimulation.

The

purpose of debt expansion is important because the moment the supposed

stimulus wears off or interest rates rise, we will see bank credit for

households and businesses begin to contract again. Only this time, there

will be a heightened risk for banks of collateral failure. And higher

interest rates will also undermine mark-to-market values for government

and corporate bonds on their balance sheets, which could rapidly erode

the capital of Eurozone banks, given their exceptionally high gearing

shown in Table A above.

Figure

3 charts the euro system’s combined balance sheet since August 2008,

the month Lehman failed, when it stood at €1.43 trillion. Greece’s

financial crisis ran from 2012-2014, during which time the balance sheet

expanded to €3.09 trillion, before partially normalising to €2.01

trillion. In January 2015, the ECB launched its expanded asset purchase

programme (APP — otherwise referred to as quantitative easing) to

prevent price inflation remaining too low for a prolonged period. The

fear was Keynesian deflation, with the HICP measure of price inflation

falling to -0.5% at that time, despite the ECB’s deposit rate having

been already reduced to -0.2% the previous September.

Between

March 2015 and September 2016, the combined purchases by the ECB of

public and private sector securities amounted to €1.14 trillion,

corresponding to 11.3% of euro area nominal GDP. The APP was

“recalibrated” in December 2015, extended to March 2017 and beyond, if

necessary, at €60bn monthly. And the deposit rate was lowered to -0.3%.

Not even that was enough, with a further recalibration to €80bn monthly

in March 2016, with it intended to be extended to the end of the year

when it would be resumed at the previous rate of €60bn per month.

The

expansion of the ECB’s balance sheet led to the rate of price inflation

recovering to 1% in 2017, as one would expect. With the expansion of

credit for the non-financial private sector going nowhere (Figures 1 and

2 above), the Keynesian stimulus simply failed in this objective. But

when in March 2020 the US Fed reduced its funds rate to 0% and announced

QE of $120bn monthly, the ECB did what it had learned to do when in a

monetary hole: continue digging even faster. March 2020 saw the ECB

increase purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) and adopt a

new programme, the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). These

measures are the reason why the volumes of the Eurosystem’s monthly

monetary policy net purchases are higher than ever before, driving its

balance sheet total to over €8.5 trillion today.

The ECB’s bond

purchases closely matched the funding requirements of national central

banks, both being €4 trillion between January 2015 and June 2021. The

counterpart to these purchases is an increase in the amount of

circulating cash. In other words, the ECB has gone full Rudolf

Havenstein. There is no difference in the ECB’s objectives compared with

those of Havenstein when he was President of the Reichsbank following

the First World War; a monetary policy that impoverished Germany’s

middle classes and pushed the labouring class and elderly into

starvation by collapsing the paper-mark. Except that today, German

society is paying through the destruction of its savings for the

spendthrift behaviour of its Eurozone partners rather than that of its

own government.

The ECB now has an additional problem with price

inflation picking up globally. Producer input prices in Europe are

rising strongly with the overall Eurozone HICP rate for November at 4.9%

annualised, and doubtless with more rises to come. Oil prices have

risen over 50% in a year, and natural gas over 60%, the latter even more

on European markets due to a supply crisis of its governments’ own

making.

Increasingly, the policy purpose of the ECB is no longer

to stimulate the economy, but to ensure that spendthrift member state

deficits are financed as cheaply as possible. But how can it do that

when on the back of soaring consumer prices, interest rates are now

going to rise? Clearly, the higher interest rates go, the faster the ECB

will increase its balance sheet because it is committed to not just

covering every Eurozone member state’s budget deficit but the interest

on their borrowings as well.

But there’s more. In a speech on 12

October, Christine Lagarde, the President of the ECB indicated that it

stands ready to contribute to financing the transition to carbon

neutral. And in a joint letter to the FT, the President of France and

Italy’s Prime Minister called for a relaxation of the EU’s fiscal rules

so that they could spend more on key investments. This is a flavour of

what they said:

"Just as the rules could not be allowed to stand

in the way of our response to the pandemic, so they should not prevent

us from making all necessary investments," the two leaders wrote, while

noting that "debt raised to finance such investments, which undeniably

benefit the welfare of future generations and long-term growth, should

be favoured by the fiscal rules, given that public spending of this sort

actually contributes to debt sustainability over the long run."

The

rules under the Stability and Growth Pact have in fact been suspended,

and are planned to be reapplied in 2023, But clearly, these two high

spenders feel boxed in. The Stability and Growth Pact will almost

certainly be eased — being a charade, rather like the US’s debt ceiling.

The trouble is Eurozone governments are too accustomed to inflationary

finance to abandon it.

If the ECB could inflate the currency

without the consequences being apparent, there would be no problem. But

with prices soaring above the mandated 2% target that is no longer true.

Up to now, the ECB has been in denial, claiming that price pressures

will subside. But we know, or should know, that a rise in the general

level of prices is due to monetary expansion, the excessive plucking of

leaves from the magic money tree, particularly at an enhanced rate since

March 2020 which is yet to be reflected fully at the consumer level.

And in its duty to fund the PIGS government deficits, the ECB’s balance

sheet expansion through bond purchases is sure to continue.

Furthermore, if bond yields do rise, it will threaten to undermine the balance sheets of the highly geared commercial banks.

The commercial banks position

With

the economies of Eurozone member states stifled by the ECB’s management

of monetary affairs since the Lehman crisis in 2008 and by more recent

covid lockdowns, the accumulation of bad debts at the commercial banks

is a growing threat to the entire financial system. Table A above, of

the Eurozone G-SIBs’ operational gearing and their share ratings, gives

testament to the problem.

So far, bad debts in Italian and other

PIGS banks have been reduced, not by their being resolved, but by them

being used as collateral for loans from national central banks. Local

bank regulators deem non-performing loans to be performing so they can

be hidden from sight in the ECB’s TARGET2 settlement system. Together

with the ECB’s asset purchases conducted through national central banks,

these probably account for most of the imbalances in the TARGET2

cross-border settlement system, which in theory should not exist.

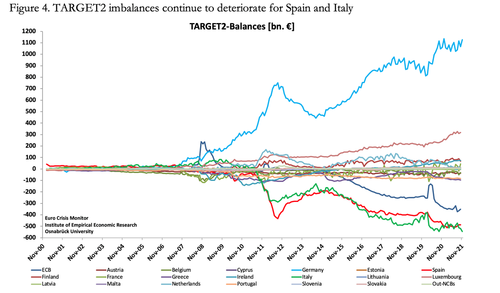

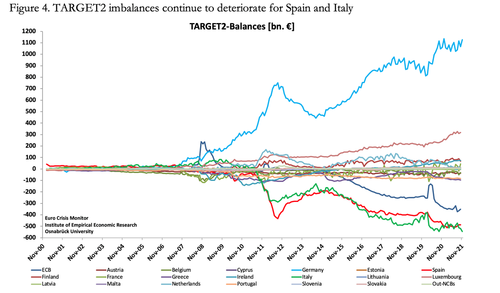

The

position to last October is shown in Figure 4. Liabilities owed to the

Bundesbank are increasing again at record levels, while the amounts owed

by the Italian and Spanish central banks are also increasing. These

balances were before global pressures for rising interest rates

materialised. Given the sharp increase in bank lending to households and

non-financial corporations since March last year (see Figure 1), bad

debts seem certain to accumulate at the banks in the coming months. This

is likely to undermine collateral values in Europe’s repo markets,

which are mostly conducted in euros and almost certainly exceed €10

trillion, having been recorded at €8.3 trillion at end-2019.[vi] The extent to which national central banks have taken in repo collateral themselves will then become a major problem.

It

is against the background of negative Euribor rates that the repo

market has grown. It is not clear what role negative rates plays in this

growth. While one can see a reason for a bank to borrow at sub-zero

rates, it is harder to justify lending at them. And in a repo, the

collateral is returned on a pre-agreed basis, so it’s removal from a

bank’s books is temporary. Nonetheless, this market has grown to be an

integral part of daily transactions between European banks.

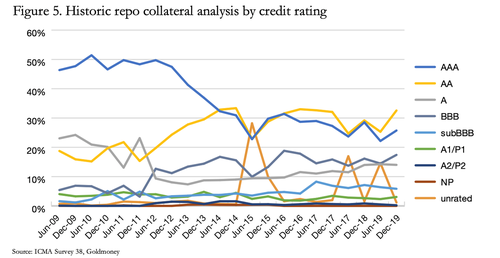

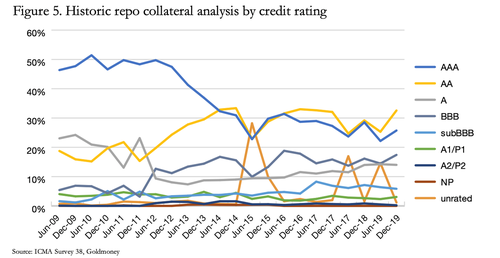

The

variations in collateral quality are shown in Figure 5. This differs

materially from repo markets in the US, which is almost exclusively for

short-term liquidity purposes and uses high quality collateral only (US

Treasury bills and bonds and agency debt).

Bonds

rated BBB and worse made up 27.7% of the total collateral in December

2019. In Europe and particularly the Eurozone rising interest rates can

be expected to undermine collateral ratings, which with increasing

Euribor rates will almost certainly contract the size of the market.

This heightens the risk of a liquidity-driven systemic failure, as repo

liquidity is withdrawn from banks that depend upon it.

Government finances are out of control

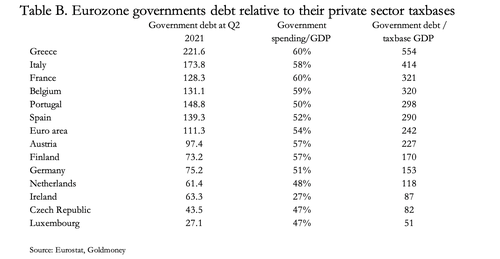

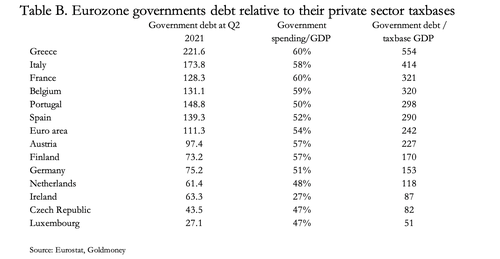

The

first column in Table B shows government debt to GDP, which is the

conventional yardstick of government debt measurement relative to the

economy. The second column shows the proportion of government spending

in the total economy relative to GDP, enabling us to derive the third

column. The base for government revenue upon which paying down its debt

ultimately rests is the private sector, and the third column shows the

extent to which and where this true burden lies.

It exposes the

impossible position of countries such as Greece, Italy, France, and

Belgium, Portugal and Spain, where, besides their own private sector

debt burdens, citizens earning their livings without being paid by their

governments are assumed by markets to be responsible for underwriting

their governments’ debts.

The hope that these countries can grow

their way out of their debt is demolished in the context of the actual

tax base. It is now widely recognised that will already high levels of

taxation further tax increases will undermine these economies.

We

can dismiss as hogwash the alterative, the vain hope that yet more

stimulus in the form of a further increase in deficits will generate

economic recovery, and that higher tax revenues will follow to normalise

public finances. It is a populist argument amongst some free marketeers

today, citing Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s successful

economic policies. But in those times, the US and UK governments were

not nearly so indebted and their economies were able to respond

positively to lower taxes. Furthermore, price inflation was declining

then while it is increasing today.

And as a paper by Carmen

Reinhart and Ken Rogoff pointed out, a nation whose government debt

exceeds 90% of GDP has great difficulty growing its way out of it.[vii]Seven

of the Eurozone nations already exceed this 90% Rubicon, and their

debts are still growing considerably faster than their GDP. At 111% the

entire Euro area itself is well above it. Taking account of the smaller

proportion of private sector activity relative to those of their

governments highlights the difference between the current situation and

that of nations that managed to pay down even higher debt levels after

the Second World War by gently inflating their way out of a debt trap

while their economies progressed in the post-war environment.

Additionally,

we should bear in mind future government liabilities, whose net present

values are considerably greater than their current debt. Over time,

these must be financed. And with rising price inflation, hard costs such

as healthcare escalate them even further. The position gets

progressively worse as these mandated costs become realised.

There

is a solution to it, and that is to cut government spending so that its

budget always balances. But for socialising politicians, slashing

departmental budgets is the equivalent of eating their own children. It

is a reversal of everything they stand for. And it requires welfare

legislation to be rescinded to stop the accumulation of future welfare

costs. There is no democratic mandate for that.

Conclusion

Rising

interest rates globally will affect all major currencies, and for some

of them expose systemic risks. An examination of the existing situation

and how higher interest rates will affect it points to the Eurozone as

being the most likely global weak spot.

The Eurozone’s debt

position pitches the entire global financial and economic system further

towards a debt crisis than generally realised. Particularly for Greece,

Italy, France, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain in that order of

indebtedness, the problem is most acute. They only survive because the

ECB ensures they can pay their bills by funding them totally through

inflation of the quantity of euros in circulation. The ECB’s entire

purpose has become to transfer wealth from the more fiscally prudent

member states to the spendthrifts by debasing the currency.

In the

process, based on figures provided by the Bank for International

Settlements the banking system is contracting credit to the private

sector, and it is not even accumulating government bonds, which is a

surprise. Much like banks in the US, Eurozone banks have become

increasingly distracted into financial activities and speculation. The

difference is the high level of operational gearing, up to thirty times

in the case of one major French bank, while most of the US’s G-SIBs are

geared about 11 times on average.

This article points to these

disparities between US and EU banking risks having been a factor in the

US repo market failure in September 2019. And we can assume that the

Americans remain wary of counterparty exposure to Eurozone banks to this

day.

That the ECB is funding net government borrowing in its

entirety indicates that even investing institutions such as pension

funds and insurance companies, along with the banks are sitting on their

hands with respect to government debt. It means that savings are not

offsetting the inflationary effects of government bond issues. It

represents a vote to stay out of what has become a highly troubling and

inflationary situation. The question arises as to how long this

extraordinary situation can continue.

It must come to an end some

time, and by destabilising a highly leveraged banking system the end

will be a crisis. With its GDP being similar in size to China’s (which

is seeing a more traditional property crisis unfolding at the same time)

a banking crisis in the Eurozone could be the trigger for dominoes

falling everywhere.

As for the euro’s future, it seems unlikely

that the ECB has the capability of dealing with the crisis that will

unfold. It has cheated the northern states, particularly Germany, the

Netherlands, Finland, Ireland, the Czech Republic, and Luxembourg to the

benefit of spendthrifts, particularly the political heavyweights of

France, Italy and Spain. It is a rift likely to end the euro system and

the ECB itself. The deconstruction of this shabby arrangement should

prove the end of the euro and possibly of the European Union itself.