This is an instructive article from Wolfstreet

Published on July 13th, 2019 that you can find on:

https://wolfstreet.com/2019/07/13/my-advice-to-the-fed-on-low-inflation-use-different-index-tell-bls-to-be-less-aggressive-with-hedonic-quality-adjustments/

Why inflation is higher that officially recorded?

In reality, as explained, the Fed, and every other financial authorities could restate inflation to announce: "Mission accomplished!"

But of course they won't. The Fed is by nature obliged to give some "room" to the government and that room takes the shape of a missing 1% of inflation per year which allows deficits to be higher than otherwise possible.

We are currently in a deflationary period thanks to technology and globalization. This means that whatever inflation we have is entirely manufactured. One day this will end, resources will become scarce again and inflation will explode. Until then, let's enjoy the ride!

The Fed could instantly claim victory and pocket the kudos.

For the first time in history, the Fed is officially and vocally considering the use of monetary policy to increase inflation, or at least inflation expectations. On Friday, it was the turn of Chicago Fed President Charles Evans to drill this message into the minds of recalcitrant consumers and workers, whose fruits of their labor get eaten up by inflation:“Because inflation expectations seem to be below our 2% objective and it’s been stubborn…it tells me our current setting for policy is on the restrictive side,” he told reporters. He sees two rate cuts this year, of 25 basis points each, not because the economy needs it, but to hammer into consumers and workers that their hard-earned dollars weren’t losing their purchasing power fast enough, and that they should change their attitude and gratefully expect more inflation.

But the problem isn’t that there isn’t enough consumer price inflation. There’s plenty. Everyone has their stories. Inflation is different for everyone. When your rent rises 10%, and 50% of what you earn goes to rent, and when in addition, your health insurance premium rises 30%, and 20% of what you earn goes to health insurance, no matter how you look at it, you’ve got a shitload of inflation on

your hands.

And so that you can deal with this increase in your costs of living, there is 3% wage inflation, hahahahaha….

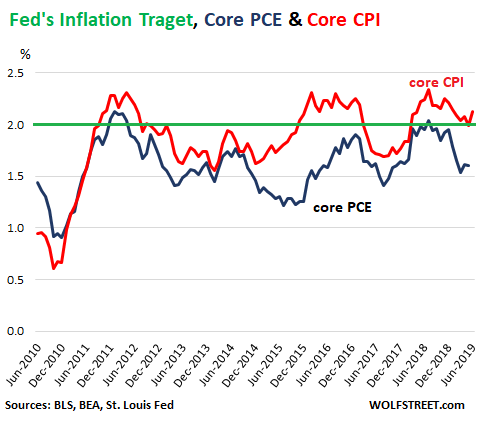

The consumer price inflation index the Fed uses as yardstick for its 2% “price stability” target is the PCE index. This index usually shows the least inflation of the major indices. And the Fed focuses on the PCE index without food and energy because those two categories are highly volatile; food and gasoline prices can surge and plunge.

The Fed’s target is “symmetrical,” as it keeps saying, meaning that inflation can be a little above or below target without triggering a monetary response.

Then there is the Consumer Price Index, or CPI. It too comes with a “core” version without food and energy, which makes it a lot less volatile. The CPI is usually higher than the PCE index.

There are constant complaints about CPI – that it doesn’t reflect the full brunt of increases in costs of living that consumers and workers experience. As mentioned above, everyone experiences inflation differently, and no one is going to be happy with any national average, but that’s what we’ve got.

Nevertheless, core CPI is a notch less unrealistic than core PCE. The chart shows core PCE (blue) and core CPI (red), and the Fed’s target (green). Note how the red line (core CPI) has been slightly above or below the Fed’s target in a fairly “symmetrical” manner since the Great Recession. If the Fed chooses core CPI as its target, its mission of “2% price stability” is accomplished, and would have been accomplished for years, and it can pocket the global kudos for “accomplishing” its mission:

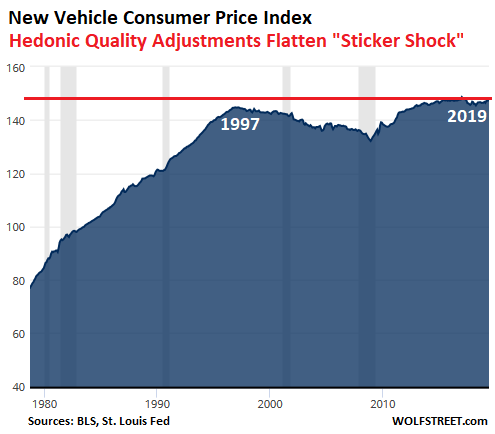

To further improve the Fed’s success ratio, after switching its yardstick to core CPI, the Fed could have harangued the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which puts the CPI together, to be less aggressive with “hedonic quality adjustments.”

The “hedonic quality adjustments” make sense on a conceptual level. For example, with cars. They are a lot better today in myriad ways than they were in 1980. Performance, comfort, safety (multiple airbags, side-impact protection bars, crumple zones, antilock brakes, traction control, warning systems, etc.), electronics to dream of in the 1980s, backup cameras, suspension systems, emission control systems, materials, durability, etc. All this costs money to develop and build.

So if new cars get better year after year, this additional cost, as it is added to the price of the car, is conceptually not inflation because you’re getting a better product, and so you’re paying more for it. Your cost of living goes up, but you’re presumably safer and more comfortable and get better quality of life.

This is a key thing about inflation: If your cost of living goes up because you’re buying higher quality products, the portion attributed to the costs of higher quality is not inflation: Yes, life gets more expensive, but it gets better presumably, and that part is not inflation. Inflation is when the same thing with the same qualities gets more expensive.

So price increases that are based on product improvements are adjusted out of the inflation index. These “hedonic quality adjustments” for new vehicles are based on these factors, according to the BLS: Reliability, durability, safety, fuel economy, maneuverability, speed, acceleration/deceleration, carrying capacity, comfort or convenience, and added or deleted equipment.

This gives us a situation where new vehicle prices show essentially no inflation since 1997, while actual transaction prices have surged:

Conceptually, I get these quality adjustments. But they’re applied to many items, such as consumer electronics and the biggie, housing costs (rent and “owners’ equivalent rent of primary residence,” meaning a nicer apartment, house, or condo). And even slightly aggressive quality adjustments, spread across the items in the basket, have a significant impact in the peculiar world of judging the Fed, where folks labor over one or two-tenth of a percentage point – say, an annual inflation rate of 1.8% (below target = Fed failed) versus 2.0% (on target = Fed succeeded).

But these quality adjustments are aggressive – and likely overly aggressive by enough to where actual inflation is understated by some relatively small amount that makes a huge difference with regards to monetary policy where a change of five-tenth of a percentage point can cause Fed judgers to go into hyperventilation, especially on the undershoot side.

So the Fed needs to first switch its yardstick from core PCE to core CPI, which would solve just about all of its current “low inflation” problem in one fell swoop.

And then, once the switch is accomplished, the Fed needs to lay out the data points for the BLS to be less aggressive in its quality adjustments. Just a tad here and there. And core CPI, even with today’s price data, would be uncomfortably high above the Fed’s target and “low inflation” would be vanquished.

The Fed could claim victory on the “low inflation” front and pocket the kudos and build its iron-clad credibility that it will always vanquish “low inflation.” And then, it could switch its rhetoric back to fretting over how to contain inflation, and how this spurt in inflation was just “transitory,” or whatever.

No comments:

Post a Comment