This is a long and sometimes technical article. But to understand why we will have a reset sooner than later, it is a must read.

The 2008 crisis was a warning shot which could have gone very bad. Somehow the system survived another decade until we reached the end of the line in 2019. In this respect, the Covid crisis was not an accident but the opportunity to flood the system with large scale financing and literally "buy" another few years.

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

Globally, further falls in consumer price inflation are now unlikely

and there are yet further interest rate increases to come. Bond yields

are already on the rise, and a new phase of a banking crisis will be

triggered.

This article looks at the factors that have come together to drive interest rates higher, destabilising the entire global banking system.

The contraction of bank credit is in its early stages, and that alone

will push up interest costs for borrowers. We have an old fashioned

credit crunch on our hands.

A new bout of price

inflation, which more accurately is an acceleration of falling

purchasing power for currencies, also leads to higher interest rates. Savage bear markets in financial and property values are bound to ensue, driving foreign investors to repatriate their funds.

This

will unwind much of the $32 trillion of foreign investment in the fiat

dollar which has accumulated in the last fifty-two years. And BRICS’s deliberations for replacing the dollar as a trade settlement medium could not come at a worse time.

Global banking risks are increasing

Gradually,

the alarm bells over credit are beginning to ring. Monetarist and

Austrian School economists are hammering the point home about broad

money, which almost everywhere is contracting. It is overwhelmingly

comprised of deposits at the commercial banks. And this week, even

China’s command economy has had credit problems exposed, with another

large property developer, Country Garden Holdings missing bond payments.

A

global cyclical downturn in bank credit is long overdue, and that is

what we currently face. Empirical evidence of previous cycles,

particularly 1929—1932, is that fear can spread though the banking

cohort like wildfire as interbank credit lines are cut, loans are called

in, and collateral liquidated. The question arising today is whether

the current credit cycle downturn is more acute than any of those faced

by our fiat currency world since the 1970s, or whether timely expansions

of central bank liabilities can come to the rescue again.

The

problem with using monetary policy to avert a financial crisis is that

there is bound to come a time when it fails, particularly when it is

driven by bureaucrats whose starting point is an assumption that banks

are adequately capitalised for an economic downturn. This ignores

unproductive debts from previous cycles which have simply accumulated

into a potential tsunami of defaults. When it overwhelms the banks, the

policy response can only be so destructive of the currency that the cure

exacerbates the problem. And with bond yields rising again, there are

good reasons to believe that a tipping point is now upon us.

Credit,

which is synonymous with the towering mountains of debt is all about

faith: faith in monetary policy, faith in the currency, and faith in a

counterparty’s ability to deliver. Before we look at risks faced by the

fiat currency cohort, it is worth listing some of the factors that can

lead to the collapse of a credit system:

Contracting bank credit.

Contracting bank credit is the consequence of the bankers recognising

that lending risks are escalating. It is an acute problem when bank

balance sheet leverage is high, magnifying the potential wipe-out of

shareholders’ capital arising from bad and doubtful debts. Consequently,

both normal and overindebted borrowers whose cash flow has been hit by

higher interest rates are denied loan facilities, or at the least they

are rationed at a higher interest cost. Therefore, the early stages of a

credit downturn see interest rates rising even further leading to

business failures. Essentially, the central banks lose control over

interest rates.

Interbank counterparty risks. There

is a long history of banks suspecting that one or more of their number

has become overextended or mismanaged and is therefore a counterparty

risk. Banks have analytical models in common to determine these risks,

so there is a danger that the majority of banks will share the same

opinion on a particular bank at the same time, leading to it being shut

out of wholesale markets. When that happens, it cannot fund deposit

outflows, is forced to turn to the central bank for support, or it

suddenly collapses. Recently, this was the fate of Silicon Valley Bank. A

downgrade by a credit agency, such as S&P or Fitch, could trigger

an interbank lending crisis, either at a local or international level in

the case of a country downgrade. These downgrades have now started.

Rising bond yields. Banks

usually stock up on government debt, redeploying their assets when they

are cautious about lending to the private sector. Therefore, an

increase in bond holdings tends to be countercyclical with reference to

the credit cycle, with exposure limited to maturities of only a year or

two. This pattern has been broken by central banks suppressing interest

rates to or below the zero bound at a time of prolonged economic

stagnation. Again, Silicon Valley Bank serves as an example of how this

can go horribly wrong. It was able to fund bond purchases at close to

zero per cent to buy Treasury and agency debt of longer maturities to

enhance the credit spread. When interest rates began to rise, the bank’s

profit and loss account took a hit, and at the same time, the market

values of their bond investments fell substantially, wiping out its

balance sheet equity. The Fed has taken on this risk by creating the

Bank Term Funding Programme, whereby the Fed takes in Treasuries at

their redemption value in return for cash in a one-year swap.

Essentially, the problem in the US is covered up and accumulating on the

Fed’s balance sheet instead — though this is not reflected in the Fed’s

accounting practices. The draw-down in this facility is currently $107

billion and rising.

Quantitative tightening. Collectively,

the major central banks (the Fed, ECB, BoJ, and PBOC) have reduced

their balance sheets by some $5 trillion since early-2022. This QT has

been put into effect by not reinvesting the proceeds of maturing

government debt. Nearly all of the reduction in the central banks’

balance sheets is reflected in commercial bank reserves, which are

balances recorded in their accounts as assets. Accordingly, the

commercial banking system as a whole comes under pressure to reinvest

the released reserves into something else, or to reduce its combined

liabilities to depositors, bondholders, and shareholders. Initially, the

commercial banking system can only respond by increasing holdings of

three and six months treasury bills, which is an unstable basis for

government funding.

Collateral liquidation. All

the charts of national bond yields scream at us that they are

continuing to rise, instead of stabilising and eventually going lower as

the majority of market participants appear to beleive. Furthermore,

with oil and other energy prices now rising strongly, the prospect of

yet higher interest rates driven by contracting bank credit (as detailed

above) along with a number of other factors discussed in this article

point to significantly higher bond yields driving a bear market in

financial assets and property values. Where banks hold collateral

against loans, there will be increasing pressure on them to sell down

financial assets before their values fall further.

Property liabilities. Bank

lending for residential and commercial property will have to absorb

substantial write-offs from the consequences of interest rates driven

higher by price inflation and contracting bank credit. The Lehman crisis

was about lending and securitisation of mortgage debt. This time,

higher interest rates will add commercial real estate into the equation.

Shadow banks. Shadow

banks are defined as institutions which recycle credit rather than

create it for which a banking licence is required. It includes pension

funds, insurance companies, brokers, investment management companies,

and any other financial entity which lends and borrows stock or deals in

derivatives and securities. All these entities present counterparty

risks to banks and other shadow banks. Some of the risks can emerge from

unexpected quarters, as was illustrated by the pension fund blow-up in

the UK last September.

Derivatives. Derivative

liabilities come from global regulated markets, which are assessed by

the Bank for International Settlements to have an open interest of about

$38 trillion last March with a further $60 trillion notional exposure

in options. Markets in unregulated over-the-counter derivatives are far

larger, at an estimated $625 trillion at end-2022 comprised of foreign

exchange contracts ($107.6 trillion) interest rate contracts ($491

trillion) equity linked ($7 trillion), commodities ($2.3 trillion), and

credit including default swaps ($9.94). All derivatives have chains of

counterparty risk. We saw how a simple position in US Treasuries

undermined Silicon Valley Bank: a failure in the derivative markets

would have far wider consequences, particularly with regulators being

unaware of the true risk position in OTC derivatives because they are

not in their regulatory brief.

Repo markets. In

all banking systems, some more than others, banks depend on repurchase

agreements to ensure their liquidity. Low interest rates and the

availability of required collateral feature in this form of funding.

Particularly in Europe, repo quantities outstanding have built up in

various currencies to over €10.4 trillion equivalent according to the

International Capital Markets Association. Essentially, these amounts

represent imbalances within the financial system, which being

collateralised have become far larger than the traditional overnight

imbalances settled in interbank markets. Even though repos are

collateralised, the consequences of a counterparty failure are likely to

be far more concerning to the stability of the banking sector as a

whole. And with higher interest rates, a bear market in collateral

values seems set to dry up this liquidity pool.

Central bank balance sheets. Central

banks which have implemented QE have done so in conjunction with

interest rate suppression. The subsequent rise in interest rates has led

to substantial mark to market losses, wiping out their equity many

times over when realistically accounted for. Central banks claim that

this is not relevant because they intend to hold their investments to

maturity. However, in any rescue of commercial banks, their technical

bankruptcy could become an impediment, undermining confidence in their

currencies.

Looking at all these potential areas for

systemic failure, it is remarkable that the sharp rise in interest rates

so far has not triggered a wider banking crisis. The failures of Credit

Suisse and a few regional banks in the US are probably just a warm-up

before the main event. But when that time arrives, it becomes an open

question as to whether central banks and their governments’ treasury

ministries will pursue bail-in procedures mandated in G20 members’ laws

in a knee-jerk response to the Lehman crisis. Or will they resort to

bailouts as demanded by practicalities? Lack of coordination on this

issue between G20 nations could jeopardise all banking rescue attempts.

Additionally,

while technicians in central banks have some understanding of credit

and the practicalities of banking, the same cannot be claimed of bank

regulators. They rarely have hands-on experience of commercial banking.

They devise stress tests, the starting assumption of which is that banks

regulated by them will survive. Otherwise, they will be demonstrated to

have failed in their duties as regulators. It is noticeable how the

economic assumptions behind prospective banking stresses are almost

always unrealistically mild.

When the muck hits the fan, the

bureaucratic imperative is to deflect all blame of the failure to the

commercial banks themselves, away from their own incompetence.

The US banking system’s weak points

As

the reserve currency for the entire global fiat currency system, the

dollar and all bank credit based upon it is likely to be the epicentre

of a global banking crisis. If other currencies weaken or fail, there is

likely to be a temporary capital flight towards the dollar before

financial contagion takes over. But if the dollar fails first, all the

rest fail as well.

The condition of the US banking system is

therefore fundamental to the global economy. There are now signs that

not only is US bank credit no longer growing but is contracting as well.

The

chart above is the sum of all commercial bank deposits plus reverse

repurchase agreements at the Fed. While the latter are technically not

in public circulation, they have been an alternative form of deposits

for large money market funds that otherwise would be reflected in bank

deposits. Recently, having soared from nothing when the Fed permitted

certain non-banks to open repo accounts with it in 2021, to a high of

$2,334.3 billion last September, the facility has subsequently declined

by $543 billion. Adding this change into the bank deposits figures shows

the true contraction of bank credit to be $1,203 billion, which is 5.9%

of the high point earlier this year. Some of the difference in bank

liabilities has been taken up by an increase in loans to commercial

banks ($556 billion) which is understandable when depositors earn

virtually nothing on their deposits compared with fixed loans to a

bank.

When these factors are considered, total assets are not yet

significantly below their peak, indicating that so far banks have been

only rearranging their assets with a view to controlling risk.

Therefore, the credit crisis it is still in its early stages, which the

potential to increase significantly.

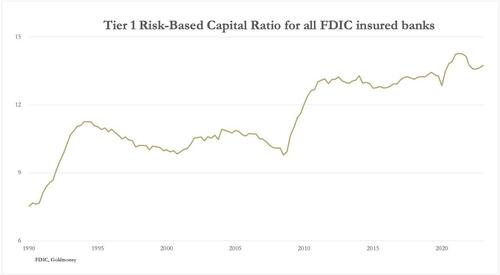

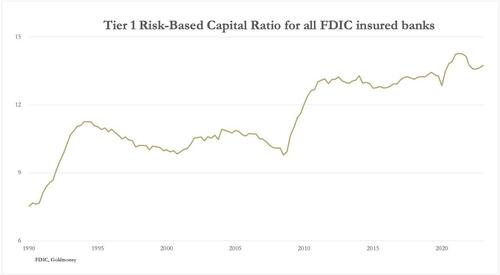

The chart below indicates why in a deteriorating lending environment banks are sure to contract their balance sheet totals.

Over

the last three decades, the ratio of total assets to tier 1 risk

capital has grown from just under eight times, which historically was

considered as normal, to a recent fourteen times. It is this leverage

ratio that threatens to wipe out shareholders’ capital if the combined

level of non-performing loans and mark-to-market write-offs on financial

investments increases from here.

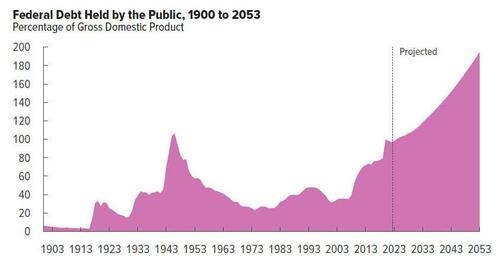

A second weak point is the US’s

dependency on foreign dollar short-term holdings including bank

deposits, which according to the US Treasury totalled $7,122 billion

last May. Of that total, $2,367 billion are bank deposits, being 13% of

the total in the US banking system. But to the total of short-term

holdings must be added long-term holdings of $24,788 billion for a grand

total of short and long-term investments of almost $32 trillion. This

is substantially in excess of US GDP and has accumulated as a result of

two related factors. Since the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, the

dollar has been the reserve currency, and internationally commodity

prices have always been quoted and dealt in with dollars.

Within

living memory, accumulation of dollars in foreign hands became excessive

once before. It led to dollars being redeemed for gold, reducing US

gold reserves from 21,682 tonnes in 1948 to 9,070 tonnes in 1971, when

the run on gold led President Nixon to suspend the Bretton Woods

Agreement. Following the abandonment of Bretton Woods, to date the

dollar has lost 98% of its purchasing power measured in real, legal,

international money which is gold. Due to its reserve currency status

and persistent US trade deficits, the proportion of foreign ownership of

dollars to US GDP has continued to grow. But recent geopolitical events

are threatening to reverse that trend.

As dollar bond yields

rise, undermining the capital values of the $32 trillion of

foreign-owned financial assets and bank deposits, foreigners are bound

to sell their dollar assets to avoid mounting losses. And already, we

see many foreign nations which are not allied with America beginning to

take evasive action. It is rumoured that next week there will be up to

60 nations attending the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, all seeking an

alternative to the dollar’s hegemony. Russian state media has clearly

stated that a new gold-backed trade settlement currency is on the

summit’s agenda, calling an end to the dollar’s fiat currency regime.

Whatever

comes out of the summit, it is clear that the fiat dollar regime has

almost run its course. The withdrawal of credit from the US economy will

undermine the currency, increase the rates of US producer and consumer

price inflation, and therefore drive up bond yields. Financial asset and

property values which have become dependent on cheap finance will take a

massive hit, serving to encourage additional foreign selling of

non-financial assets. The losses for banks, not just in the US, are set

to rapidly escalate.

Undoubtedly, banks will come under pressure

to bail out the US Government from a further deterioration of its

finances at a time when foreigners are more interested in selling US

Treasuries than buying them. To an extent, substituting dodgy loans to

the private sector for government debt is attractive to the banks, but

only with very short-term maturities. The consequence will be that

government financing of maturing Treasuries and of new issues will be

facilitated by 3-month and 6-month T-bills, which can be regarded as

near-cash. The inflationary consequences are one thing, but the impact

of rising interest rates due to the dollar being sold down by foreign

agents will intensify the debt trap by rapidly increasing debt funding

costs.

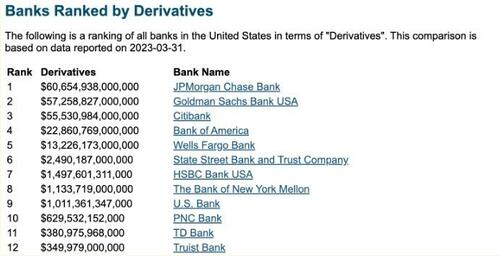

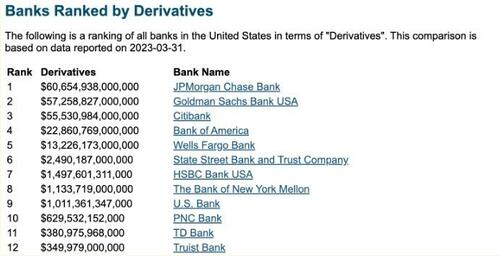

As if this is not enough, at the same time the collapse of

bank credit is bound to act negatively on derivative obligations. The

table below is a snapshot of OTC obligations for the top twelve US

banks.[i]

For

the reader losing count of all the noughts, it should be noted that for

the top nine their exposure is in the trillions. While it is true that

some OTC derivatives, such as credit and credit default swaps are not

obligations for their notional amounts, others such as foreign exchange

derivatives, commodity, and equity-linked contracts ($117 trillion) are

extinguished for the full amount. But they are only recorded on bank

balance sheets as insignificant contract values.

For example, in

the BIS derivative estimates quoted earlier in this article, the

notional value of foreign exchange OTC contracts last December was

$107.576 trillion with a gross market value of $4.846 trillion. It is

the latter figure which is the basis recorded in bank balance sheets.

But even that total is further reduced by being listed as a net balance

of purchase and sold obligations, reducing apparent exposure to an even

smaller figure. Essentially, over $107 trillion of assets and

liabilities are made to disappear.

According to the BIS’s 2022

triennial OTC derivatives survey, the US dollar is a component of 88.5%

of this FX position. Other than offshore trading between non-US banks in

Eurodollars, which is a minor proportion of the total, all dollar

contracts have US banks as counterparties. This gives rise to two

systemic threats. The first and most obvious is counterparty failure

with a foreign bank or shadow bank. Obviously, with rising interest

rates and collapsing financial asset values in collateral, the risk of

counterparty failure from outside the US banking system will increase.

The second counterparty failure comes from contracts between two US

banks or shadow banks.

We can be sure that central bankers (if not

bank regulators) are fully aware of these risks, refusing to draw

public attention to them. For confirmation, we saw the Fed rescue AIG in

September 2008 in an $85 billion bailout. AIG was the world’s largest

insurance company at that time, and an originator of credit default

swaps and other derivative obligations. There were other factors

involved, such as securities lending. But clearly, for the Fed to rescue

an insurance company must have reflected the Fed’s concerns about AIG’s

failure as a counterparty in the CDS market.

The new BRICS gold currency

Next

week, we will know more about the proposal being presented at the BRICS

summit in Johannesburg. All the indications are that this new

settlement currency will be denominated in a quantity of gold, such as

gold grammes. The return of gold backed credit is an important

development for the growing BRICS family and all the member nations,

dialog partners and associates of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

seeking a better alternative to the US dollar. Furthermore, it is now in

Russia’s strong interest to undermine the US dollar, lifting oil and

gas dollar prices to stabilise a falling rouble.

The extent to

which the plan for a new gold denominated currency is credible seems set

to undermine the dollar’s value expressed in commodities, goods, and

services externally in addition to the domestic economic and monetary

factors mentioned above. The foreign exchanges will begin to anticipate

that dollar reserves held by central banks in the growing BRICS camp

will become increasingly redundant, to be replaced with the new gold

trade settlement currency. Sovereign wealth funds are bound to follow by

reducing their dollar balances, as will international commodity dealers

and importers.

Not only will dollars be sold, but the need to

recycle them into US Treasuries and other investments will fall away.

Unless the US Government acts to radically cut its borrowing

requirements, it will face a rapidly deteriorating funding situation.

The dollar costs of commodities, raw materials and imported goods will

rise due to the dollar’s weakness. Consequently, dollar interest rates

are bound to rise to reflect the premium foreign holders will demand to

retain their dollar balances. And even that is unlikely to be enough.

The great unwind of the last fifty-two years of pure fiat dollars will

surely threaten not only the dollar’s existence, but its highly

leveraged banking system.

The discarding of the fiat currency past

for a currency or currencies more closely allied to energy and

commodities, which is actually what gold represents, is not limited to

the destruction of fiat dollars, but of all other fiat currencies as

well. For our current purposes, what also concerns us is the same threat

faced by the other major currencies: the euro, yen, and sterling.

It

has already been mentioned that an initial failure in the US banking

system will be the likely course of events because it is the most

over-owned of all the major fiat currencies. But if a banking crisis

does break out elsewhere first, it could lead to the dollar being

temporarily bought as a safe haven until financial contagion undermines

all banking relationships. It behoves us to look at the position in

these other major currencies. And the example we will take is of the

issues which face banks in the Eurozone.

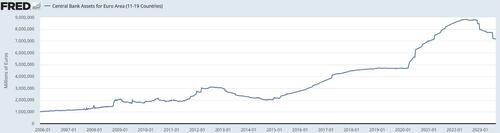

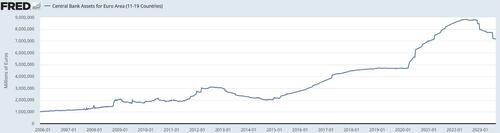

The euro system

In

common with other major central banks, the ECB and its network of

national central banks, together the euro system, have accumulated

government and other bonds through quantitative easing. The extent to

which it has boosted the size of the euro system balance sheet and

subsequently declined is shown in the chart below.

Having

hit a high point of €8,828 billion fifteen months ago, the ECB’s and

national central banks’ combined assets have declined to €7,167 billion.

Most of the increase from the last financial crisis to the peak had

been through what the ECB calls asset purchase programmes, but otherwise

known to us as quantitative easing. The decline in total assets has

been achieved by allowing short-term assets to mature and for the funds

to be not reinvested, leading to the liabilities to commercial banks

being reduced.

Nevertheless, on the remaining securities holdings

totalling €4,865 billion currently, there are significant losses on a

mark-to-market basis. Assuming an average maturity of five years, and an

average rise in yield from 0% to 3.2% on Eurozone government bonds,

over the last year the losses in the euro system amount to about €700

billion. This is nearly six times the combined euro system’s equity. The

valuation problem is concealed by euro system accounting, which values

bonds on a straight line basis between purchase price and final

redemption value.

To assume that this is not a problem because the

ECB can always print euros is complacent. The only hope for the

Eurosystem is for bond yields to decline, and therefore values to rise

restoring balance sheet integrity. But for now, yields are rising, and

it is becoming clear that they will continue to rise. At some stage, the

assumption that inflation will return to target and that interest rates

and bond yields will decline will be abandoned, and the

recapitalisation of the entire euro system will then have to be

contemplated.

It will not be easy. Undoubtedly, legislation at a

national level in multiple jurisdictions will be required. It is one

thing for the ECB to railroad its inflationary policies through despite

protests from politicians in Germany and elsewhere, but begging for

equity capital puts the ECB on the back foot. Questions are bound to be

raised in political circles about monetary policy failures, and why the

TARGET2 imbalances exist. The whole recapitalisation process could

descend into a very public dispute, particularly since national central

banks may need capital injections as well before they can recapitalise

the ECB in proportion to their shareholder keys.

Yet, Europeans

rely upon the euro system to backstop the entire commercial banking

network, whose global systemically important banks (GSIBs) are even more

leveraged than the American banks. Furthermore, there are bound to be

hidden Eurozone equivalents of Silicon Valley Bank, whose balance sheets

have been undermined to the point of insolvency by the unexpected rise

in interest rates and the collapse in bond values. The €10 trillion repo

market also faces collapsing collateral values. Eurozone GSIBs have

heavy exposure to derivative counterparty risks. Yet, the euro system

itself is bankrupt, having paid top euros for bonds which have been

sinking faster than a tropical sun at twilight.

It is in the

nature of a banking crisis that several factors come together in an

unexpected perfect storm. We will all be wise after the event. But for

now, we can only observe the disparate strands likely to come together

and destroy the euro system, its commercial banks, and possibly the euro

itself.

That is, if the US banking system doesn’t collapse first.