Here's a great example in the article below of the Dunning Kruger effect where a little knowledge leads to poor conclusions. In this case it is data without understanding the context which unfortunately is what we see almost everywhere nowadays as data has become easily available while context still takes time to grasp,

Japan and the UK have very little in common but fine, historical parallels can indeed be helpful to understand the past. But can past data help us understand the future? Mostly no but to some extant population data is the exception.

In the case of Japan. Reality is unfortunately far worse than the data suggests.

In most countries birth rates are much higher in the countryside than in the cities. Not in Japan mostly thank to the very high average age outside the urban areas, often above 60. This means that whatever incentives the government proposes the effect will be minimum.

Likewise in the city centers, birth rates are extremely low, below 1 child per women just as in Hong Kong or in Korea. There too, incentives will have little effect because the high price of real estate is a natural limitation that few young couples can overcome.

We are left with the endless suburbs where most younger people live. But even there, high incentives will change little, maybe a few percents at most. If people saw an increase of purchasing power, which is very unlikely in the current inflationary environment, they would either move closer to downtown or upgrade their home to a larger one before having a second child.

So the downward trend of the Japanese population will not slow but will conversely accelerate which is by the way already what we are seeing. The number of birth in Japan in 2022 was below 800,000 which is the number which was expected for 2030 not so long ago.

To some extent, this diminution of the population will necessarily be compensated by an increase of immigration. This is already the case although because Japan does not offer easily long term residency to foreigners, all the recent arrivals from China and Asia are not counted in official statistics. Still, whatever the number of immigrants is, it won't be able to compensate the dramatic fall of the population which will soon be above 1 million per year!

Japan has a problem of excessive debt as well as of having exported abroad too much of its industrial infrastructure. To this, we will soon have to add a crashing population. So Japan's GDP which already shrank from 15.6% of the world GDP in 1992 to 5.9% in 2020 will see a further decline in the years ahead. This is unavoidable.

By Russell Clark, author of the Capital Flows and Asset Markets substack,

Japanese demographics is often cited in the secular stagnation story, and particularly by bond bulls.

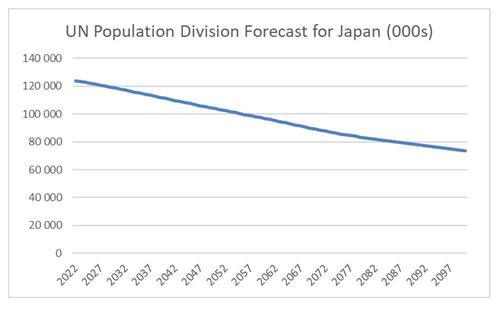

The UN’s Population Division has a forecast for Japanese population to fall below 80m by the end of the century.

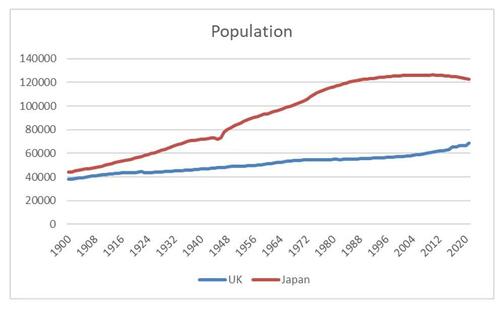

I think it is unlikely that Japanese population falls that far, but first of all you need to understand how unusual Japan is demographically. Japan only has a land mass 50% greater than the UK. In arable land terms, the UK has 50% more than Japan, reflecting the far more mountainous terrain in Japan. 120 years ago, Japan and the UK had similar sized populations, but then Japanese population grew rapidly, while the UK stagnated. If you ever visit Japan, you will notice on train trips between cities that ever single bit of flat land is used. This really gives the impression that Japanese overpopulated their island, and now need to see their population fall.

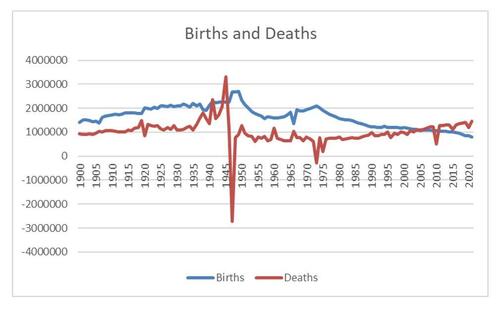

I can get Japanese population and birth statistics back to 1900, and assuming relatively low (to none) immigration, work out births and deaths by year. A few surprising features is how Japanese births peaked soon after WWII. While there was another rise in the 1970s, it was very low compared to number births before WWII. Intriguingly, 1947 and 1972 show negative deaths. This is reflecting the repatriation of 6 million Japanese citizens from former colonies in Taiwan, Korea and Manchuria, and the return of Okinawa respectively. So after the trauma of World War II, mainland Japanese population actually grew at the end of World War II due to repatriation.

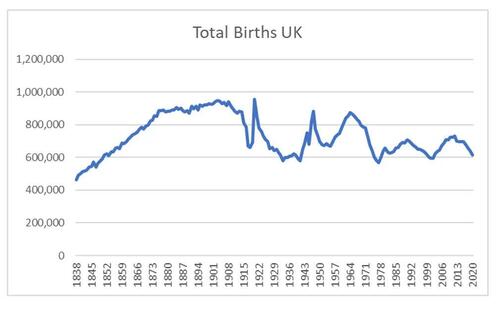

For comparison, the UK saw peak births, in 1901. If there is a demographic crisis, its has been brewing for a very long time. The rise in the UK population is mainly due to net migration. Both Japan and UK saw a countertrend rise in the 1960s and 1970s, which I think was due to pro-labour policies - but I will leave that aside for the moment.

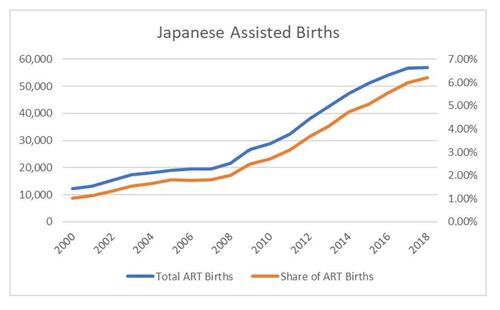

The first part of my argument for a change in birth rates is that changes in technology means that women can have children later. In this area, Japan is a leader. In the last available data I have, 6% of all Japanese births, which is far higher than any other large country.

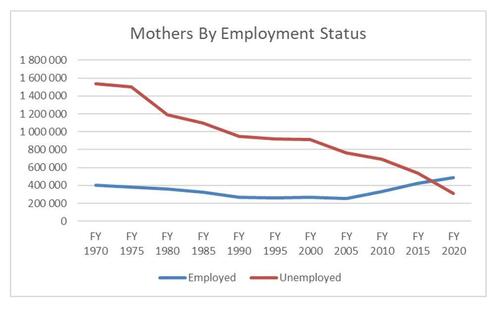

For me ART births take away age as a constraint on fertility rates. Technology means that women well into their 40s and even 50s can now have children if they want and can afford it. And here we see another positive trend in Japanese fertility rates. Working mothers are having more children are having more children than non-working mothers, after being the minority for years.

Another possible pro-labor shift that could reverse fertility trends is the work-from-home shift. I speak from personal experience that working from home is far more conducive to raising children than office based working. I also know that childcare in Japan is both expensive, and culturally women were expected to quit work to have children, as the above chart shows (at least until relatively recently). As we have seen with recent government actions on green energy, once a crisis is declared, governments can quickly accelerate trends. At some point, fertility rates in Japan will be declared a “real crisis”, and policies of free IVF, and free childcare will transform fertility rates. I very much doubt Japanese population will fall below 100 million people.

No comments:

Post a Comment