Well, not exactly but still, time is not what we believe it is. To understand this, we need to start with the Bell theorem which stipulate that my time is different than yours and the two can only be reconciled at the speed of light but not faster. (Except for the spooky action at a distance of quantum entanglement but let's not get into this. It is proven but nobody truly understands why!)

And then, worse, far worse, Einstein theory of relativity has consequences. One of these is called the Pole and Barn Paradox. Take a 10m long pole and sent it at close to the speed of light through a barn which is only 5m wide. Well, when you close the two doors, at one instant t, the pole fits within the barn. This of course is well explained by relativity as the pole actually shrinks in size as its speed approaches the speed of light. But there is another way to understand it: The pole has now a 45 degree angle in time which explains why it is now no longer than 5m and therefore fits within the two doors of the barn. In other word; there is no instant t. Only t1 and t2.)

Understand this paradox and suddenly your concept of "time" will change completely. Time in reality is not a dimension because it is infinitely malleable. In other words, as Einstein proved, time is not absolute but relative, to space but more fundamentally to what happens within this space.

So unlike what we have been enticed to believe, time travel is not possible. The future does not exist yet. It depends on events which have not happened yet and which are still uncertain. As for the past, it is worse: There is no past! Only a chain of events in one specific place. When you look at the stars, you see them now as they were when light started its journey. Well, our present and their present cannot be reconciled faster than the speed of light as we explained before, which has a direct consequence. For a star 300 light-year away from us, their present and our present will never be connected faster than in 300 years. The Universe does not understand the concept of an instant t.

Time is local, not global.

by Makai Allbert via The Epoch Times

A minute is always a minute, except when it isn’t.

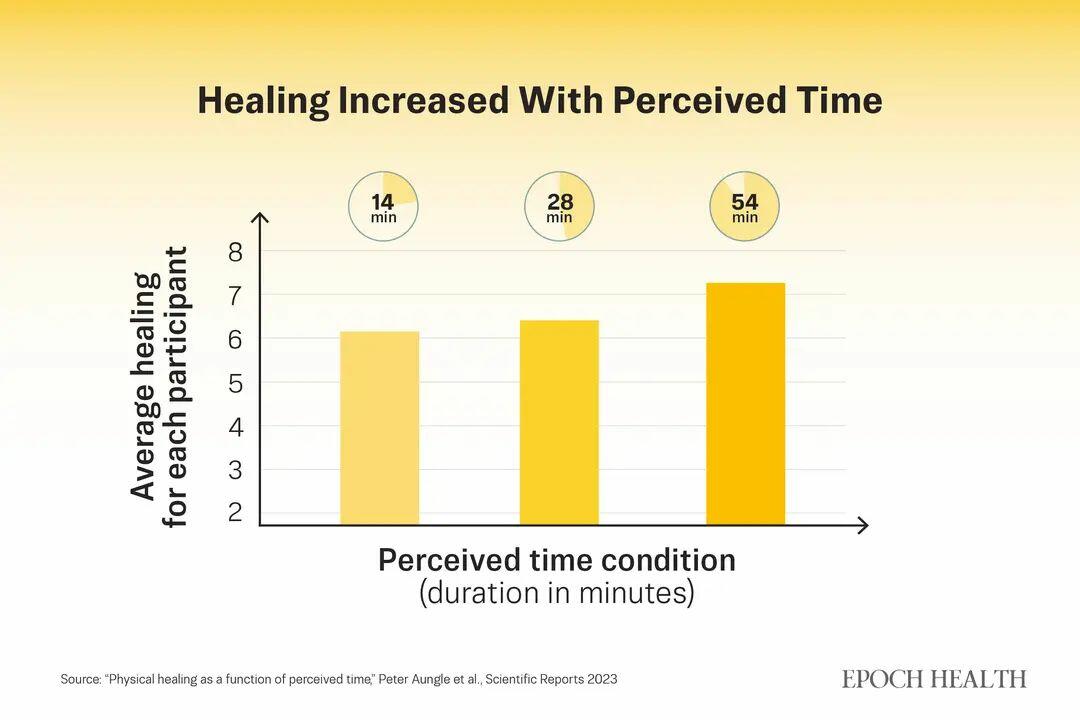

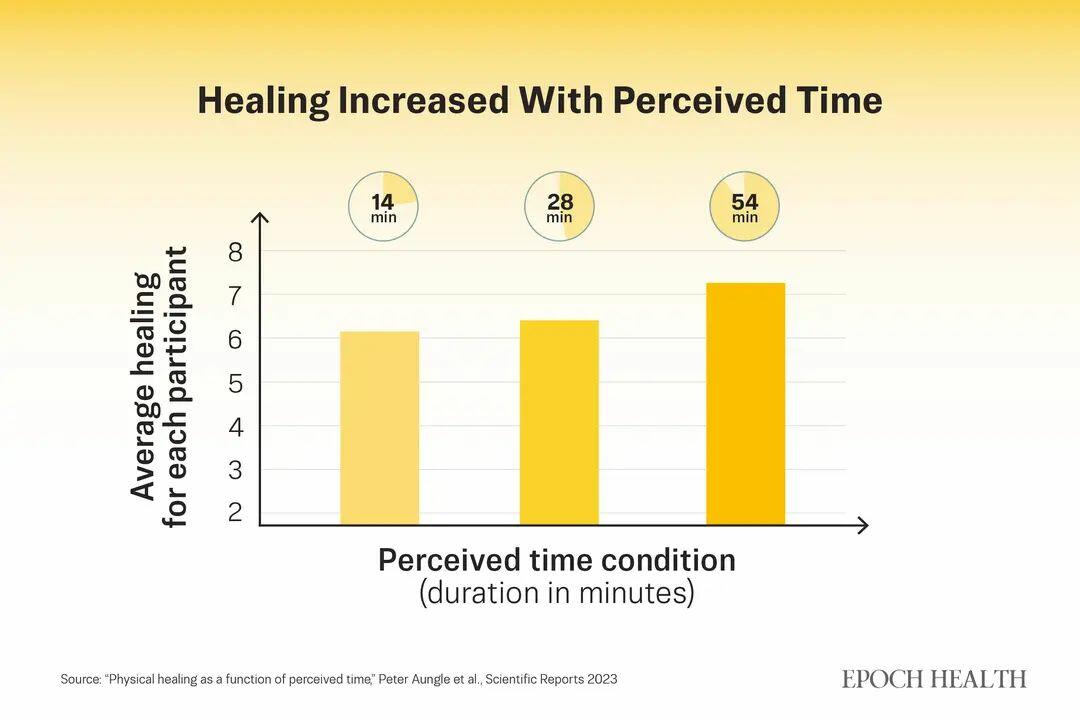

This idea was put to the test in a 2023 Harvard study. Researchers induced minor bruising on participants’ forearms and then had them sit in rooms where the clocks ran at normal speed, half-speed, or double-speed.

Crucially, the actual elapsed time was identical across all conditions—28 minutes—but the clocks ticked at different rates.

The results surprised the researchers. Wounds healed faster when people thought more time had passed, and slower when they thought less time had passed. “Personally, I didn’t think it would work,” lead author Peter Aungle told The Epoch Times. “And then it did work!”

A century ago, Albert Einstein demonstrated that time is relative—not fixed. He explained the idea with a simple, humorous example: “Put your hand on a hot stove for a minute, and it seems like an hour. Sit with a pretty girl for an hour, and it seems like a minute. That’s relativity.”

Now, psychologists and neuroscientists are finding that our sense of time is not only inherently subjective but also highly malleable.

We can’t stop the clock, but by understanding how we perceive time, we can make minutes feel longer, heal faster, and even expand our memories.

How the Mind Affects Reality

The Harvard healing experiment is a pivotal piece of evidence that mind and body are not only connected, but may be one and the same. “We weren’t really manipulating time itself. We were manipulating expectations,” Aungle said.

“If they [people] think more time has passed, they expect more healing—and those expectations can shape the body.”

Most people think of mind-body effects only in terms of emotion, he added. Yet, “psychology is embedded in everything the body does. I would argue the mind influences every physiological outcome to some degree.”

Expectations are not the only time bender. While believing time has sped up aids healing, high-arousal negative emotions, such as fear, significantly dilate our perception of time, making it feel slower.

In one study, participants watched frightening clips from “The Shining” or “Scream.” Afterward, a blue circle was presented in the center of the computer screen. Participants perceived that the circle lasted longer after watching frightening movies than after watching neutral or sad films.

Sylvie Droit-Volet, the lead researcher of the study, told The Epoch Times that subjective expansion is likely because “fear accelerates the internal clock, making time seem to pass more quickly and prompting action”—the fight or flight response.

Because the internal clock is ticking faster, measuring more units of time per second, the external world appears to move in slow motion. The time dilation allows the brain to process information with higher resolution during life-threatening situations.

Slowing Time

We can also make time feel longer in positive ways, such as by seeking out moments of awe.

A 2012 study published in Psychological Science found that feeling awe, whether from a story or a memory, makes time feel more abundant.

Awe acts as a reset button for the brain. It brings people intensely into the present moment. According to the “extended-now theory,” focusing on the present moment elongates time perception because we are not mentally rushing toward the future. By filling the present with vastness, awe offsets the feeling that time is slipping away, making life feel more satisfying.

The study also found that people who felt awe were less impatient, more willing to help others, and preferred experiences over material products.

We can also slow our perception of time through the practice of savoring.

“Savoring is putting a highlighter pen on our experiences,” psychologist Tamar Chansky told The Epoch Times. Savoring does not require extra duration, but rather a shift in attention.

For the time-starved, Chansky suggested taking “two more bites” of an experience—whether tasting coffee or looking out a window—to engage the brain’s awareness. This simple act creates “invisible, little expanders” within our finite days. It is a way of feeding the spirit without requiring a restructuring of one’s schedule, she said.

“We could rush through a whole day so easily ... and we might feel somewhat or even very productive at the end of the day, but we might not feel good. So finding these little pockets ... helps us to feel that expansion within.”

Chansky’s insight aligns with research findings that training attention, such as through meditation, can change how we perceive time.

Experienced meditators feel time passes more slowly during meditation and in their daily lives than people who do not meditate.

Being in nature also slows our experience of time.

In one study, participants overestimated the duration of a walk by nearly two minutes when it took place in nature, whereas their estimates were accurate for urban walks. Nature exposure increases mindfulness and reduces stress, states that are theoretically linked to a slowing of the internal clock. If you need to “buy” yourself a little time, you can find it in the wild. “Time grows on trees,” the study concluded.

Memories and Time

Why do childhood summers feel endless while adult years appear to fly by? The answer lies in how our brains process novelty. Our brains measure time based on how many new memories are created.

When we encounter unexpected stimuli, our brains process more information, leading to a subjective expansion of that duration. In experiments where a low-probability stimulus—called an oddball—appears in a stream of repetitive standard stimuli, the oddball, or novelty, is consistently judged to last longer.

“The more unique, meaningful, or changing experiences we have, the longer the stretch of time feels in memory,” Marc Wittmann, a research fellow at the Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health in Germany, said. On the other hand, routine compresses time in memory by halting the recording of details it already knows. When neurons fire repeatedly in response to the same stimulus, their response diminishes; they become efficient but record less data.

Therefore, to stretch your subjective life, introduce variation.

“A fulfilled and varied life is a long life,” Wittmann told The Epoch Times. This effect is not about simply filling a schedule with busyness—it is about “deep emotional resonance with the world.” A hundred days of routine collapse into a single memory unit in the brain; a week of travel or new experiences remains distinct and expansive.

Wittmann’s recent research adds a nuance: cognitive capacity also plays a role. As we age, the perception that the last decade flew by is partly due to cognitive decline, which affects our ability to encode complex memories. However, this effect is moderate. People who stay mentally and physically fit and continue to seek novel, emotionally rewarding experiences can subjectively expand their sense of time, regardless of age.

Read the rest here...

No comments:

Post a Comment