The world as seen from a small but still significant island. (Great article!)

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

Britain’s next Prime Minister must address two overriding problems: London

is at the centre of an evolving financial and currency crisis brought

forward by a change in interest rate trends; and the reality of emerging

Asian superpowers must be accommodated instead of attacked.

This article starts by examining the economic challenges the next Prime Minister faces domestically.

Are the two candidates equipped with a strategy to improve the nation’s

economic prospects, and why can we expect them to succeed where others

have failed?

It is unlikely that either candidate

is aware that there has been a fundamental shift in the direction of

interest rates, the consequences of which are undermining debt mountains

everywhere. The problem is particularly acute for the euro

system. As well as for other major currencies, London operates as the

clearing centre for transactions between the Eurozone’s commercial

banks. If the euro system fails, London’s survival as a financial centre

could be jeopardised.

The other major challenge is geopolitical.

Being tied into America’s five-eyes intelligence network, coupled with

policies to remove fossil fuels as sources of energy Britain is

condemned to falling behind the Asian superpowers, and sacrificing

trading relationships with which her true interests must surely lie.

And then there were two…

The

selection process for a new Conservative Prime Minister has whittled it

down to two — Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss. The former is a wealthy

meritocrat, former Goldman Sachs employee and hedge fund manager, the

latter a self-made woman. Sunak was Chancellor (finance minister). Among

several other high-office roles, Truss has been First Secretary to the

Treasury. Both, in theory at least, should understand government

finances. Both studied PPE at Oxford, so are certain to have been

immersed in the Keynesian version of economics, which also informs

Treasury thinking.

Despite their common Treasury experience and

being on that same page, Sunak’s and Truss’s pitches on economic affairs

have been very different. Sunak aims to maintain a balanced budget,

reducing taxes afterwards as economic growth increases tax revenues.

This is Treasury orthodoxy. Truss is claiming she will cut taxes more

immediately in an emergency budget to stimulate growth. She is emulating

the Thatcher/Reagan supply-side playbook.

The politics are

straightforward. The electorate is comprised of about 160,000 paid up

Conservative Party members, mostly leaning towards less government, free

markets, and lower taxes. As a subset of over 40,000,000 voters

nationwide, they may be reasonably representative of a silent majority

in the middle classes which believe in conservative societal values.

The

one issue that matters above all for Conservative Party members is

taxes. Given their different stances on tax, Truss has emerged as the

early favourite. Furthermore, to the disadvantage of Sunak very few

Chancellors make it to Prime Minister for a reason: like Sunak, they

nearly always push the Treasury line on maintaining balanced budgets

over the cycle, which means that they are for ever trying to pluck the

goose for more tax with the minimum of hissing. Don’t expect geese to

willingly vote for yet more exfoliation.

The issue of less

government in the total economy is not properly addressed by either

candidate or is restricted to vague promises to do something about

unnecessary bureaucracy. In arguing for free markets, Truss is stronger

in this respect than Sunak who appears to be more captured by the

permanent establishment.

With the exception of Treasury ministers,

all politicians in office are naturally inclined to seek increased

departmental budgets, which is a problem for all tax cutters. But to

understand the practical difficulties of reducing government spending,

we must make a distinction between departmental expenditure limits and

annually managed expenditure. The former is budgeted for by the Treasury

in its allocation of financial resources. The latter can be regarded as

including additional costs arising from public demand for departmental

services. This explains why total departmental expenditure for fiscal

2020-21 was £566.2bn, representing about half of total government

spending of £1,112bn.

With government spending split 50/50

overall on departmental expenditure limits and public demands for

services, both issues must be addressed when reducing costs

meaningfully. Failing to do so means only departmental expenditure

limits are tackled, resulting in less resources to deliver mandated

public services. That would be seen by the opposition and the public to

be a government failing. Therefore, it is not sufficient to merely say

to ministers that they must cut departmental expenditure, but laws and

regulations must also be changed to reduce public service obligations as

well. That takes time.

Imagine tackling this problem with respect

to the National Health Service. The NHS takes 34% of total departmental

expenditure limits, yet it clearly fails to efficiently provide the

public with the services required of it. Health ministers always argue

that it needs more financial resources. This is followed by education

(13% of total departmental expenditure). What do you do: sack teachers?

And Scotland at 8% is another no-go area, where cuts would likely

encourage the nationalist movement. And that is followed to a similar

extent by defence spending at a time of a proxy war against Russia…

One

could go on about other ministry spending and the costly provision of

their services, but it should be apparent that any realistic cuts in

public services are likely to be minor and overwhelmed by rising and

unbudgeted departmental input costs which are indirectly the consequence

of the Bank of England’s monetary policies. It is therefore hardly

surprising that neither Sunak nor Truss is seriously engaged with the

subject of reducing state spending, merely fluffing around the topic.

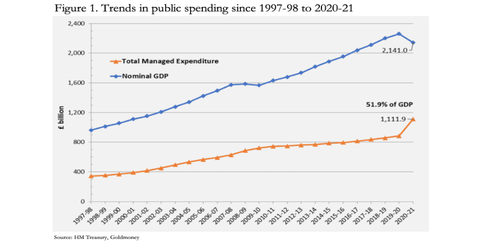

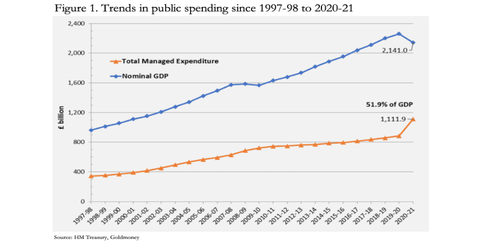

But

total state spending is going to be an overriding problem for the

future PM. Figure 1 shows the long-term trend of total managed

expenditure relative to GDP, admittedly exacerbated by covid. Since

then, there has been a recovery in GDP to £2,239bn in the four quarters

to Q1 2022, and covid related disbursements have materially declined, so

that in the last fiscal year, total government spending is estimated to

have dropped to 46.5% of GDP from the high point of 51.9%.

However,

rising interest rates globally are set to drive the UK economy into

recession. Even if the recession is mild, while GDP falls this will

increase public spending on day-to-day public services back up to over

50% of GDP.

The philosophical problem for the new PM can be summed

up thus: with half the economy being unproductive and the productive

economy shouldering the burden, how can economic resources be restored

to producers in a deteriorating economic outlook?

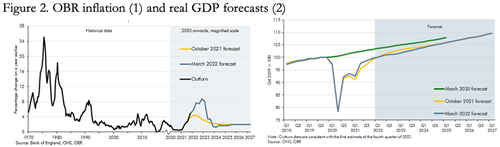

Inflation is not going away

Orthodox

neo-Keynesians in the government and its (supposedly) independent

Office for Budget Responsibility do not recognise that the root of the

inflation problem is the debasement of currency and credit. Furthermore,

by thinking it is a short-term supply chain problem, or a temporary

energy price spike due to sanctions against Russia, the OBR, in common

with the Bank of England takes the view that consumer price rises will

return to the targeted 2% level. Only, it might take a little longer

than originally thought.

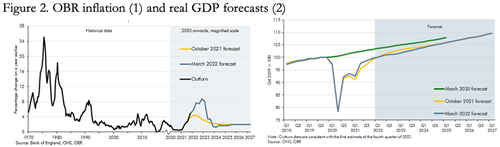

Figure 2 shows the OBR’s latest forecasts (in March) for inflation (panel 1) and real GDP (panel 2).

Note

how the October forecast failed to reflect an annual CPI rising to more

than 4%. In March that was raised to 8%, which is already outdated.

Price inflation rising to over 10% is on the cards, and it should be

noted that the retail price index, abandoned by government because of

the cost of using it for indexation, already shows annual consumer

inflation to be rising at 11.8%.

The OBR’s response to these

unwelcome developments is simply to push out an expected return to the

2% inflation target a little more into the future. Similarly, it expects

the trajectory of GDP growth will be maintained, having just slipped a

little.

On this evidence, the OBR’s advice to a future prime

minister and his chancellor will be badly flawed. Instead of going down

the macroeconomic approach of modelling the economy, instead we need to

apply sound, unbiased economic and monetary theories.

We know

that the Bank of England’s monetary policies have debased the currency,

reflected inevitably in a falling purchasing power for the pound. That

is what drives the increase in the general level of prices. The primary

cause is not, as government and central bank officials have stated,

supply chain disruptions and the consequences of the war in Ukraine.

That has only made things worse, in the sense that higher energy and

commodity prices along with supply bottlenecks have encouraged the

average citizen to adjust the ratio of personal liquidity to purchases

of goods and services, bringing forward purchases and driving prices

even higher. The debasement of fiat currencies everywhere is encouraging

their users to dump them in what appears to be a slowly evolving

crack-up boom encouraged by a background of product shortages.

The

common view that consumer price inflation is a temporary phenomenon is

little more than wishful thinking, as is the latest argument developing,

that rising interest rates will deflate economic demand. The official

line is that lower demand will lead to lower prices. Realistically, less

demand is the product of less supply, so it does not lead to lower

prices. And here we must turn to the second panel in Figure 2, of the

OBR’s modelling of real GDP.

With the annual increase in the RPI

already at 11.8% and that of the CPI at 9.1%, a bank rate of 1.25% fails

to recognise the changed environment. Interest rates, bond yields and

therefore the cost of government funding are all set to rise

substantially. The consequences for financial assets will be to drive

their market values lower. And unprofitable businesses relying on

finance for their existence risk being wiped out, either because they

will lose hope of ever being economic, or bank credit will be withdrawn

from them.

All empirical evidence is that currency debasement

accompanies the destitution of an economy. Therefore, it is a mistake to

think that a slump in business activity will neutralise the inflation

problem. To deal with the inflation problem, the new prime minister will

have to resist intervening and let all failing businesses go to the

wall. But whoever becomes PM, there is no mandate to simply let events

take their course. Instead, the burden of sustaining a failing economy

will certainly lead to a soaring fiscal deficit — financed, of course,

by yet more monetary debasement.

Without quantitative easing, the

appetite of commercial banks for financing the fiscal deficit at a time

of rising bond yields is uncertain. It is a different environment from a

long-term trend of declining interest rates, underwriting bond prices. A

trend of rising interest rates is likely to lead to funding

dislocations, as we saw in the 1970s. Furthermore, commercial banks have

more urgent problems to deal with, which is our next topic.

Banks will be in self-preservation mode

GDP

is no more than a measure of currency and credit in qualifying

transactions. Growth in nominal GDP is a direct consequence of an

increase in currency and bank credit, particularly the latter. An old

rule of thumb was credit was larger than currency in the ratio of

perhaps ten to one. The evolution of banking, the war on cash, and the

advent of debit cards have changed that, and since covid, the ratio has

increased to 37:1.

This means that changes in nominal GDP are

almost entirely dependent on the supply of bank credit for the

production of goods and services. The availability of customer deposits

to draw down for spending reflect the commercial banking network’s

willingness to maintain the asset side of their balance sheets,

comprised of lending and financial investment. Customer deposits, which

are a bank’s liabilities, will contract if bank lending, recorded as a

bank’s assets, contract. This is already evident in the slowing down of

broad measures of money supply growth.

Given that bank balance

sheets are highly leveraged, and that the economic outlook is

deteriorating, bank lending is almost certainly beginning to contract.

This vital point appears to be completely absent in the OBR’s modelling

of the economic outlook.

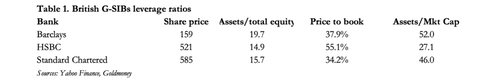

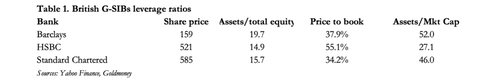

By the usual metrics, commercial banks

are extremely over-leveraged after thirteen years of the current bank

credit cycle, in other words since the Lehman failure. Table 1 below

summarises the position of the three British G-SIBs (designated global

systemically important banks). They can be regarded as a banking proxy

for exposure to global systemic risks.

Important

points to note are that balance sheet leverage, the relationship of

assets to total equity, are as much as double multiples of between eight

and twelve times at the top of a normal bank credit cycle. Balance

sheet equity includes accumulated undistributed profits as well as the

common equity entitled to them.[i] All three banks’ common shares trade at substantial discounts to their book value.

Their

share prices tell us that markets have assessed that there is a high

level of systemic risk in these banks’ shares. It would be extraordinary

if the directors of these banks are blind to this message. Before covid

when economic dangers were less apparent, it would have been

understandable though not necessarily excusable for them to use this

leverage to maximise profits, particularly since all banks were

following similar lending policies.

Covid came, and all banks had

no option but to extend loan facilities to businesses affected, for

fear of triggering substantial loan losses on a scale to take down the

banks themselves. Furthermore, the government put in loan guarantee

schemes. Post-covid, bankers face the withdrawal of government loan

guarantees, rising interest rates and the consequences for their risk

exposure to higher interest rates, as well as declining values for

mark-to-market financial assets — the latter affecting both bank

investments and collateral against loans.

Clearly, the cycle of

bank credit is on the turn and will contract. The dynamics behind this

phase of the cycle indicate that to take leverage back down to more

conservative levels the contraction will have to be severe. But an

excessive restriction of credit both causes and produces a run for cash

notes and gold. And thus, without intervention banks and businesses all

collapse in a universal crash.

With very little of GDP recorded

in pound notes and coin, as a statistic it is driven overwhelmingly by

the quantity of bank credit outstanding. In a credit contraction the GDP

statistic will collapse — unless the Bank of England takes upon itself

the replacement of credit in a massive economic support programme.

The

consequences are sure to undermine government finances badly. Sunak’s

hope that a balanced budget can be maintained, let alone permit him to

oversee tax cuts when government finances permit, becomes a fairy tale

when tax revenues slump and spending commitments increase. So, too, is

Truss’s belief that immediate tax cuts will benefit economic growth and

restore tax revenues. The reality of office is likely to decree fiscal

policies very different being those being touted by both candidates.

The impending collapse of the euro system

I wrote recently for Goldmoney about the inevitable crisis developing in the euro system, here.

Since that article was published, the European Central Bank has raised

its deposit rate to zero and instituted a rescue package for the highly

indebted PIGS in its awkwardly named Transmission Protection Instrument.

In plain language, the ECB will continue to buy PIGS government debt to

ensure their yields do not rise much further relative to benchmark

German bunds.

It is increasingly clear that the euro system is in

deep trouble, caught out by the surge in consumer price inflation.

Rising interest rates, which have only just started, will undermine

Eurozone commercial bank balance sheets because they obtain much of

their liquidity by borrowing through the repo market.[ii] TARGET2

imbalances threaten to collapse the system from within as the interest

rate environment changes. The ECB and its shareholding network of

national central banks all face escalating losses on their bonds, which

earlier this month I calculated to be in the region of €750bn, nearly

seven times the combined euro system balance sheet equity.

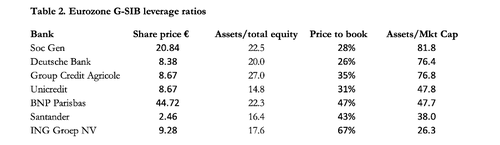

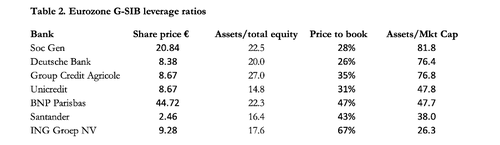

Not

only does the whole euro system require to be refinanced, but this is at

a time when the Eurozone’s G-SIBs are even more highly leveraged than

the three British ones. Table 2 updates the one in my article referred

to above.

With

the average Eurozone G-SIB asset to equity ratios of over 20 times, the

euro’s G-SIBs are one of the two most highly leveraged networks in

global banking, the other being Japan’s. The common factor is negative

interest rates imposed by their central banks. The consequence has been

to squeeze credit margins to the extent that the only way in which banks

can sustain profit levels is to increase operational gearing.

Furthermore, an average balance sheet leverage of over 20 times does not

properly identify systemic risks. Bank problems come from extremes, and

we can see that at 27 times, Group Credit Agricole should concern us

most in this list. And we don’t see all the other Eurozone banks trading

internationally that don’t make the G-SIB list, some of which are

likely to be similarly exposed.

The problem for Britain is

twofold. Including its banks, Britain’s financial system is more exposed

to Eurozone risks than any other, and a Euro system failure would be a

catastrophe for it. Furthermore, Eurozone banks and fund managers use UK

clearing houses for commercial euro settlements. Counterparty failures

will contaminate systemically all participants, not only dealing in

euros but all the other major currencies settled in London as well. The

damage is sure to extend to forex and credit markets, including all OTC

derivatives which are an integral part of bank clearing facilities.

At

the last turn of the bank lending cycle, it was the securitisation of

liar loans in the US which led to what is commonly referred to as the

Great Financial Crisis. This is a term I have rarely used, preferring to

call it the Lehman Crisis because I knew, along with many others, that

the non-resolution of the excesses at the time would store up for an

even greater crisis in the future. We can now begin see how it will be

manifested. And this time, it looks like being centred on London as a

financial centre rather than New York.

We must hope that a

collapse of the euro system will not happen, but there is mounting

evidence that it will indeed occur. The falling row of dominoes is

pointing at London, and it could even happen before the Conservative

Party membership have voted for either Truss or Sunak in

early-September.

Dealing with a banking crisis fall out

On

the advice of the Bank for International Settlements, following the

Lehman crisis the G20 member states agreed to make bail-ins mandatory,

replacing bailouts. This was a politically motivated move, fuelled by

the emotive belief that bailing out banks are at the taxpayers’ expense.

In fact, bank bailouts are financed by central banks, both directly and

indirectly. The only taxpayer involvement is marginally through their

aggregated savings in pension funds and insurance companies. But these

funds have been over-compensated with extra cash through quantitative

easing. The audit trail leads to the expansion of currency and credit

every time, and not to taxes as the phrase “taxpayer liabilities”

implies.

All the G20 nations have passed legislation enabling

bail-in procedures. In the Bank of England’s case, it retains discretion

to what extent bail-in as opposed to other rescue methods might be

used. As to specifics for the other G20 members it is unclear to what

extent they have retained this flexibility and understand bail-in

ramifications. And it could be an additional confusion likely to

complicate a global banking rescue, compared with the previously

accepted bail-out procedures.

In theory, a bail-in reallocates a

bank’s liabilities from deposits and loans into shareholders’ capital —

excepting, perhaps, smaller depositors covered by deposit guarantee

schemes. But even that is at the authorities’ discretion.

The

objective can only make sense for single bank, as opposed to systemic

failures. But if it were to be applied to an individual banking failure

in the current unstable situation, it would almost certainly undermine

other banks, as bank loans and other non-equity interests would be

generally liquidated, and deposits flee to banks deemed to be safer as

panic sets in. The risk is that bail-in procedures could set off a

system-wide failure, particularly of the banks rated by the market with

substantial discounts to book value — including all the UK’s G-SIBs (see

Table 1 above).

Even assuming the Bank’s bail-in procedures are

ruled out in dealing with a systemic banking crisis, to keep banks

operating will require a massive expansion of credit from the Bank of

England. In effect, the central bank will end up taking on the entire

banking system’s obligations. With London at the centre of a global

banking crisis, all other major central banks whose banking and currency

networks are exposed to it must be prepared to take on all their

commercial banking obligations as well.

Britain’s place in the world must be secured

The

problems attendant on currencies afflict all the majors, with the UK at

the centre of the storm because of its pre-eminent role in

international markets. There is no evidence that the leadership at the

Bank of England is equipped to understand and deal with an increasingly

inevitable economic and monetary crisis which will take sterling down.

Nor has there been any attempt by the Treasury to rebuild the nation’s

depleted gold reserves to protect the currency, which is a gross

dereliction of public duty.

But we must now turn our attention to

geopolitical matters, where there is currently no pragmatism in

Britain’s foreign policies. Since President Trump’s aggressive stance

against the challenge to America from Chinese technology, the UK as

America’s most important partner in the five-eyes intelligence sharing

agreement has sided very firmly with America against both Chinese and

Russian interests.

The recent history of the five-eyes partnership

is one of political blindness — ironic given its title. Wars against

terrorism, more correctly US intelligence operations which destabilise

Muslim nations before the military go in to sort the mess out have been a

staple since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. A series of wars in the

Middle East and Afghanistan have yielded America and her NATO allies

only pyrrhic victories at best, created business for the US armaments

industry, and resulted in floods of refugees attempting to enter Europe.

Meanwhile,

these actions have only served to cement the partnership between

Russia, China, and all the Asian members of the Shanghai Cooperation

Organisation amounting to over 40% of the world population. They have a

common mission to escape from the dollar’s hegemony.

America’s

abandonment of Afghanistan was pivotal. As America’s closest

intelligence partner, Britain following Brexit is no longer a direct

influence in Europe’s domestic politics. Together, these factors have

surely encouraged Putin to adopt more aggressive tactics with the

objective of undermining the NATO partnership, always seen as the

principal threat to Russia’s borders.

This is the true objective

behind his proxy war against Ukraine. Supported by Britain, the US

response has been to fuel the Ukrainian proxy war by supplying military

hardware. But the biggest mistake made by the NATO partnership has been

to impose sanctions on Russian trade.

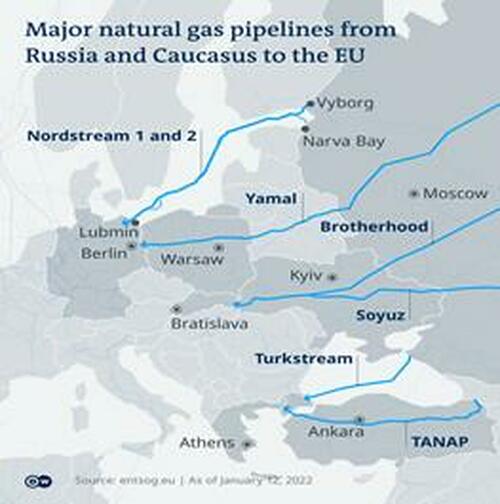

The consequences for energy

and other vital commodity prices do not bear unnecessary repetition. The

knock-on effects for global food prices and the shortages emerging

ahead of the winter months are still evolving. Sanctions have become

NATO’s suicide note — it is beginning to look like a modern version of

Custer’s last stand.

It is surely to the private horror of

Western strategists that the sense behind Putin’s strategy is emerging:

it is to further the economic consolidation of Asia with the unfettered

advantages of fossil fuels traded at significant discounts to world

prices. At their own behest, America and its NATO allies are shut out of

it entirely.

Global fears of climate change and the war against

fossil fuels are essentially a Western concept, not shared by the great

Asian powers and the Middle East. The hysteria over fossil fuel

consumption has led European nations to eliminate their own production

in favour of renewables. Consequently, to make up energy shortfalls they

have become dependent on imported oil and gas from Russia. And that is

what will split Europe away from US hegemony.

Unrestricted energy

supply is crucial for positive economic outcomes. The result of US-led

sanctions is that energy starvation faces all her allies, including

Britain and the members of the European Union. As an oil-producing

nation herself, America is less affected, her allies suffering the brunt

of sanctions against Russian energy supplies.

By committing to

policies to lessen climate change without fossil fuel sources of energy,

the economic prospects for Europe and the UK are of economic decline.

Only

last weekend agreements have been signed between Russia, Iran, and

Turkey, with Iran due to become a full member of the Shanghai

Cooperation Organisation later this year. Other than Turkey’s wider

economic interest, it is essentially about oil. In addition to these

developments, Russia’s Foreign Secretary Sergei Lavrov went on to

address the Arab League in Cairo. It is clear that Russia is building

its relationship with oil producers in the Middle East as well, whose

members are faced with declining Western markets and growing Asian

demand.

Therefore,

British policy tied into US hegemony with a self-imposed starvation of

energy is untenable. It is worse than being on the losing side. It

guarantees economic decline relative to the emerging Asian powers. A

future Prime Minister needs to pursue a more pragmatic course than the

bellicose stance against Russia and China, currently espoused by Liz

Truss. As Britain’s current Foreign Secretary, she is briefed by the

UK’s intelligence services, which are closely aligned with their

American colleagues. There is groupthink going on, which must be

overcome.

The interest rate trend and the looming threat of the

mother of all financial crises on London’s doorstep requires a

leadership strong enough to take on the civil service, always

complacent, and guide the wider electorate through some troubling times.

Following the financial and currency crisis, mindsets must be radically

changed, steered away from perpetual socialisation of economic

resources back towards free markets. Which of these two candidates for

the premiership see us through? Probably neither, though being less a

child of the establishment Liz Truss might offer a slim chance.

The

task is not impossible. Currencies have completely collapsed before,

and nations survived. Instead of being restricted to one or a group of

nations, the looming crisis threatens to take out what we used to call

the advanced economies in their entirety, so it will be a bigger deal.

Fortunately for Britain, her citizens are less likely to riot than their

continental cousins. But as a warm-up for the main event, our new

leader will have to navigate through growing discontent brought on by

rising prices, labour strikes and all the other forms of economic

pestilence which bought Margaret Thatcher to power.