This article is in the footprint of the 1972 Club of Rome report and the less apocalyptic 1997 Fourth Turning book by Strauss and Howe which both predicted a sharp inflection around the year 2020.

It is hard to predict if 2021 will see a rebound after the extreme downturn of 2020 or an acceleration of the decline. Short of a major external shock, I would go 60/40 for "rebound" as institutions and structures in the West have not yet been weakened to an extent allowing a crash. But underneath the froth of activity, the declining ROI in the energy sector is relentless. New "discoveries" will be in the 60 to 100 USD range which people simply cannot pay for.

With all the money printing, we should start seeing some inflation but the current recession destroys more money than is being created resulting in massive redistribution and misallocation of funding as most of the cash rains down close to the Eccles and Frankfurt towers. Look at Argentina and other "developing" economies as canaries in the coal mine... "Interesting times!"

Authored by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog,

Most people expect that the economy of 2021 will be an improvement from 2020. I don’t think so. Perhaps COVID-19 will be somewhat better, but other aspects of the economy will likely be worse.

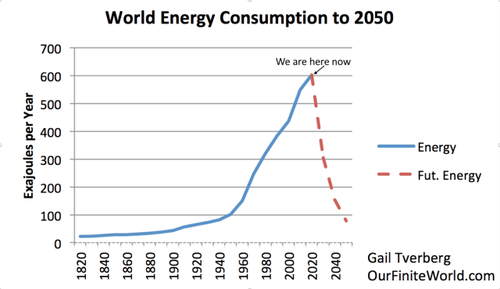

Back in November 2020, I showed a chart illustrating the path that energy consumption seems to be on. The sharp downturn in energy consumption has occurred partly because the cost of oil, gas and coal production tends to rise, since the portion that is least expensive to extract and ship tends to be removed first.

At the same time, prices that energy producers are able to charge their customers don’t rise enough to compensate for their higher costs. Ultimate customers are ordinary wage earners, and their wages are not escalating as rapidly as fossil fuel production and delivery costs. It is the low selling price of fossil fuels, relative to the rising cost of production, that causes a collapse in the production of fossil fuels. This is the crisis we are now facing.

Figure 1. Estimate by Gail Tverberg of World Energy Consumption from 1820 to 2050. Amounts for earliest years based on estimates in Vaclav Smil’s book Energy Transitions: History, Requirements and Prospectsand BP’s 2020 Statistical Review of World Energy for the years 1965 to 2019. Energy consumption for 2020 is estimated to be 5% below that for 2019. Energy for years after 2020 is assumed to fall by 6.6% per year, so that the amount reaches a level similar to renewables only by 2050. Amounts shown include more use of local energy products (wood and animal dung) than BP includes.

With lower energy consumption, many things tend to go wrong at once: The rich get richer while the poor get poorer. Protests and uprisings become more common. The poorer citizens and those already in poor health become more vulnerable to communicable diseases. Governments feel a need to control their populations, partly to keep down protests and partly to prevent the further spread of disease.

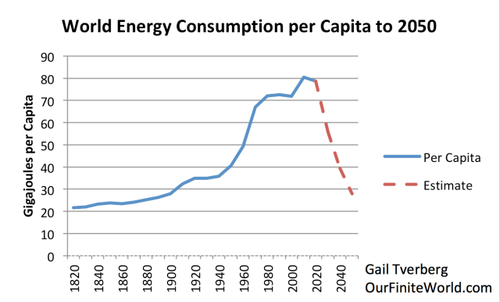

If we look at the situation shown on Figure 1 on a per capita basis, the graph doesn’t look quite as steep, because lower energy consumption tends to bring down population. This reduction in population can come from many different causes, including illnesses, fewer babies born, less access to medical care, inadequate clean water and starvation.

Figure 2. Amounts shown in Figure 1, divided by population estimates by Angus Maddison for earliest years and by 2019 United Nations population estimates for years to 2020. Future population estimated to be falling half as quickly as energy supply is falling in Figure 1. World population drops to 2.8 billion by 2050.

What Is Ahead for 2021?

In many ways, it is good that we really don’t know what is ahead for 2021. All aspects of GDP production require energy consumption. A huge drop in energy consumption is likely to mean disruption in the world economy of varying types for many years to come. If the situation is likely to be bad, many of us don’t really want to know how bad.

We know that many civilizations have had the same problem that the world does today. It usually goes by the name “Collapse” or “Overshoot and Collapse.” The problem is that the population becomes too large for the resource base. At the same time, available resources may degrade (soils erode or lose fertility, mines deplete, fossil fuels become harder to extract). Eventually, the economy becomes so weakened that any minor disturbance – attack from an outside army, or shift in weather patterns, or communicable disease that raises the death rate a bit – threatens to bring down the whole system. I see our current economic problem as much more of an energy problem than a COVID-19 problem.

We know that when earlier civilizations collapsed, the downfall tended not to happen all at once. Based on an analysis by Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov in their book, Secular Cycles, economies tended to first hit a period of stagflation, for perhaps 40 or 50 years. In a way, today’s economy has been in a period of stagflation since the 1970s, when it became apparent that oil was becoming more difficult to extract. To hide the problem, increasing debt was issued at ever-lower interest rates.

According to Turchin and Nefedov, the stagflation stage eventually moves into a steeper “crisis” period, marked by overturned governments, debt defaults, and falling population. In the examples analyzed by Turchin and Nefedov, this crisis portion of the cycle took 20 to 50 years. It seems to me that the world economy reached the beginning of the crisis period in 2020 when lockdowns in response to the novel coronavirus pushed the weakened world economy down further.

The examples examined by Turchin and Nefedov occurred in the time period before fossil fuels were widely used. It may very well be that the current collapse takes place more rapidly than those in the past, because of dependency on international supply lines and an international banking system. The world economy is also very dependent on electricity–something that may not last. Thus, there seems to be a chance that the crisis phase may last a shorter length of time than 20 to 50 years. It likely won’t last only a year or two, however. The economy can be expected to fall apart, but somewhat slowly. The big questions are, “How slowly?” “Can some parts continue for years, while others disappear quickly?”

Some Kinds of Things to Expect in 2021 (and beyond)

[1] More overturned governments and attempts at overturned governments.

With increasing wage disparity, there tend to be more and more unhappy workers at the bottom end of the wage distribution. At the same time, there are likely to be people who are unhappy with the need for high taxes to try to fix the problems of the people at the bottom end of the wage distribution. Either of these groups can attempt to overturn their government if the government’s handling of current problems is not to the group’s liking.

[2] More debt defaults.

During the stagflation period that the world economy has been through, more and more debt has been added at ever-lower interest rates. Much of this huge amount of debt relates to property that is no longer of much use (airplanes without passengers; office buildings that are no longer needed because people now work at home; restaurants without enough patrons; factories without enough orders). Governments will try to avoid defaults as long as possible, but eventually, the unreasonableness of this situation will prevail. The impact of defaults can be expected to affect many parts of the economy, including banks, insurance companies and pension plans.

[3] Extraordinarily slow progress in defeating COVID-19.

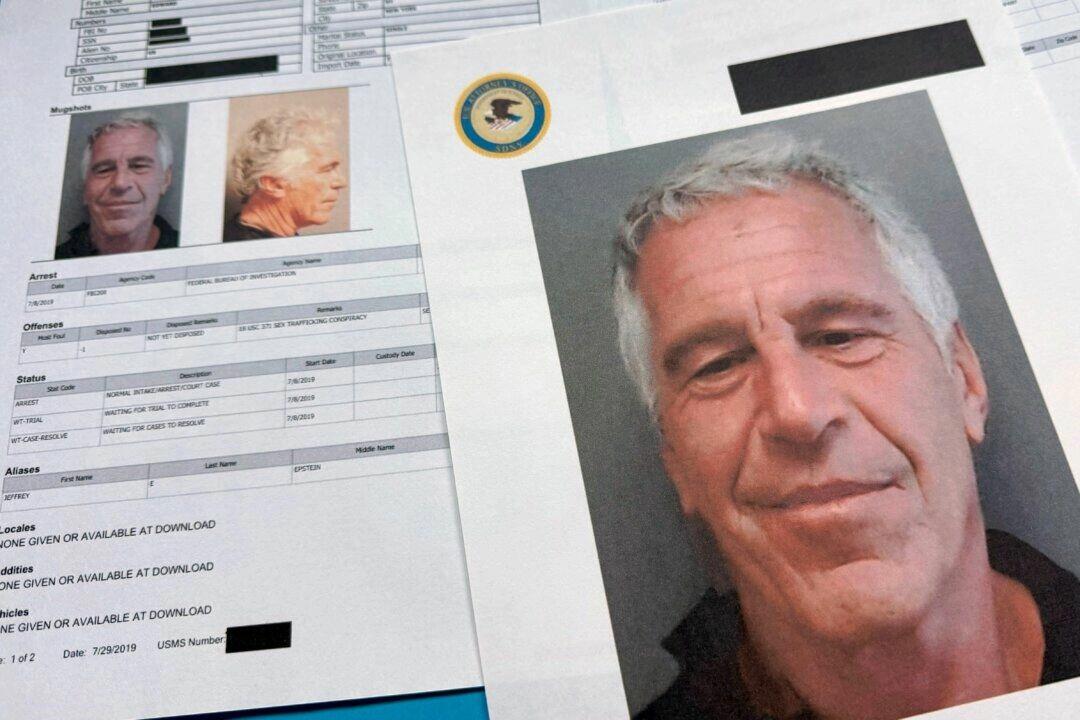

There seems to be a significant chance that COVID-19 is lab-made. In fact, the many variations of COVID-19 may also be lab made. Researchers around the world have been studying “Gain of Function” in viruses for more than 20 years, allowing the researchers to “tweak” viruses in whatever way they desire. There seem to be several variations on the original virus now. A suicidal/homicidal researcher could decide to “take out” as many other people as possible, by creating yet another variation on COVID-19.

To make matters worse, immunity to coronaviruses in general doesn’t seem to be very long lasting. An October 2020 article says, 35-year study hints that coronavirus immunity doesn’t last long. Analyzing other corona viruses, it concluded that immunity tends to disappear quite quickly, leading to an annual cycle of illnesses such as colds. There seems to be a substantial chance that COVID-19 will return on an annual basis. If vaccines generate a similar immunity pattern, we will be facing an issue of needing new vaccines, every year, as we do with flu.

[4] Cutbacks on education of many kinds.

Many people getting advanced degrees find that the time and expense did not lead to an adequate financial reward afterwards. At the same time, universities find that there are not many grants to support faculty, outside of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering or Math) fields. With this combination of problems, universities with limited budgets make the financial decision to reduce or eliminate programs with reduced student interest and no outside funding.

At the same time, if local school districts find themselves short of funds, they may choose to use distance learning, simply to save money. This type of cutback could affect grade school children, especially in poor areas.

[5] Increasing loss of the top layers of governments.

It takes money/energy to support extra layers of government. The UK is now completely out of the European Union. We can expect to see more changes of this type. The UK may dissolve into smaller regions. Other parts of the EU may leave. This problem could affect many countries around the world, such as China or countries of the Middle East.

[6] Less globalization; more competition among countries.

Every country is struggling with the problem of not enough jobs that pay well. This is really an energy-related problem. Instead of co-operating, countries will tend to increasingly compete, in the hope that their country can somehow get a larger share of the higher-paying jobs. Tariffs will continue to be popular.

[7] More empty shelves in stores.

In 2020, we discovered that supply lines can break, making it impossible to purchase products a person expects. In fact, new governmental rules can have the same impact, for example, if a country bans travel to its country. We should expect more of this in 2021, and in the years ahead.

[8] More electrical outages, especially in locations where reliance on intermittent wind and solar for electricity is high.

In most places in the world, oil products were available before electricity. On the way down, we should expect to see the reverse of this pattern: Electricity will disappear first because it is hardest to maintain a constant supply. Oil will be available, at least as long as is electricity.

There is a popular belief that we will “run out of oil,” and that renewable electricity can be a solution. I do not think that intermittent electricity can be a solution for anything. It works poorly. At most, it acts as a temporary extender to fossil fuel-provided electricity.

[9] Possible hyperinflation, as countries issue more and more debt and no longer trust each other.

I often say that I expect oil and energy prices to stay low, but this doesn’t really hold if many countries around the world issue more and more government debt as a way to try to keep businesses from failing, debt from defaulting, and stock market prices inflated. There is a danger that all prices will inflate, and that sellers of products will no longer accept the hyperinflated currency that countries around the world are trying to provide.

My concern is that international trade will break down to a significant extent as hyperinflation of all currencies becomes a problem. The higher prices of oil and other energy products won’t really lead to any more production because prices of all goods and services will be inflating at the same time; fossil fuel producers will not get any special benefit from these higher prices.

If a significant loss of trade occurs, there will be even more empty shelves because there is very little any one country can make on its own. Without adequate goods, population loss may be very high.

[10] New ways of countries trying to fight with each other.

When there are not enough resources to go around, historically, wars have been fought. I expect wars will continue to be fought, but the approaches will “look different” than in the past. They may involve tariffs on imported goods. They may involve the use of laboratory-made viruses. They may involve attacking the internet of another country, or its electrical distribution system. There may be no officially declared war. Strange things may simply take place that no one understands, without realizing that the country is being attacked.

Conclusion

We seem to be headed for very bumpy waters in the years ahead, including 2021. Our real problem is an energy problem that we do not have a solution for.