No wonder the West is going mad. It will get worse soon!

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

We

will look back at current events and realise that they marked the

change from a dollar-based global economy underwritten by financial

assets to commodity-backed currencies. We face a change from

collateral being purely financial in nature to becoming commodity based.

It is collateral that underwrites the whole financial system.

The ending of the financially based system is being hastened by geopolitical developments.

The West is desperately trying to sanction Russia into economic

submission, but is only succeeding in driving up energy, commodity, and

food prices against itself. Central banks will have no option but to

inflate their currencies to pay for it all. Russia is linking the rouble

to commodity prices through a moving gold peg instead, and China has

already demonstrated an understanding of the West’s inflationary game by

having stockpiled commodities and essential grains for the last two

years and allowed her currency to rise against the dollar.

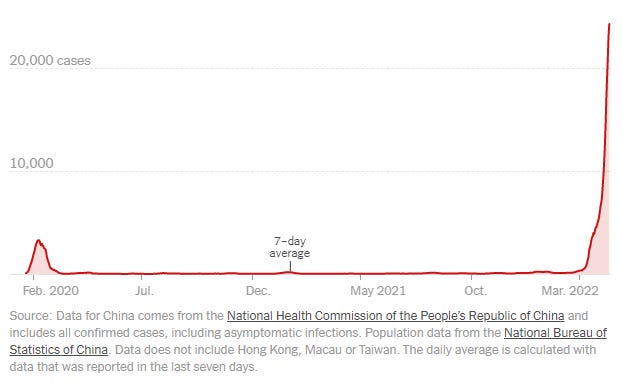

China

and Russia are not going down the path of the West’s inflating

currencies. Instead, they are moving towards a sounder money strategy with the prospect of stable interest rates and prices while the West accelerates in the opposite direction.

The

Credit Suisse analyst, Zoltan Pozsar, calls it Bretton Woods III. This

article looks at how it is likely to play out, concluding that the

dollar and Western currencies, not the rouble, will have the greatest

difficulty dealing with the end of fifty years of economic

financialisation.

Pure finance is being replaced with commodity finance

It

hasn’t hit the main-stream media yet, which is still reporting

yesterday’s battle. But in March, the US Administration passed a death

sentence on its own hegemony in a last desperate throw of the dollar

dice. Not only did it misread the Russian situation with respect to its

economy, but America mistakenly believed in its own power by sanctioning

Russia and Putin’s oligarchs.

It may have achieved a partial

blockade on Russia’s export volumes, but compensation has come from

higher unit prices, benefiting Russia, and costing the Western alliance.

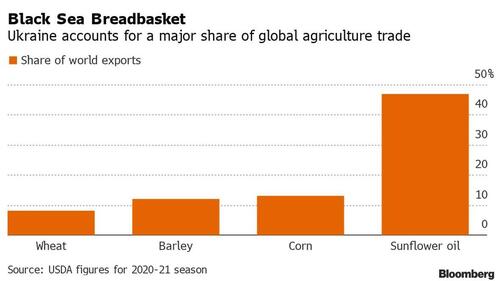

The

consequence is a final battle in the financial war which has been

brewing for decades. You do not sanction the world’s most important

source of energy exports and the marginal supplier of a wide range of

commodities and raw materials, including grains and fertilisers, without

damaging everyone but the intended target. Worse still, the intended

target has in China an extremely powerful friend, with which Russia is a

partner in the world’s largest economic bloc — the Shanghai Cooperation

Organisation — commanding a developing market of over 40% of the

world’s population. That is the future, not the past: the past is

Western wokery, punitive taxation, economies dominated by the state and

its bureaucracy, anti-capitalistic socialism, and magic money trees to

help pay for it all.

Despite this enormous hole in the sanctions

net, the West has given itself no political option but to attempt to

tighten sanctions even more. But Russia’s response is devastating for

the western financial system. In two simple announcements, tying the

rouble to gold for domestic credit institutions and insisting that

payments for energy will only be accepted in roubles, it is calling an

end to the fiat dollar era that has ruled the world from the suspension

of Bretton Woods in 1971 to today.

Just over five decades ago, the

dollar took over the role for itself as the global reserve asset from

gold. After the seventies, which was a decade of currency, interest

rate, and financial asset volatility, we all settled down into a world

of increasing financialisation. London’s big bang in the early 1980s

paved the way for regulated derivatives and the 1990s saw the rise of

hedge funds and dotcoms. That was followed by an explosion in

over-the-counter unregulated derivatives into the hundreds of trillions

and securitisations which hit the speed-bump of the Lehman failure.

Since then, the expansion of global credit for purely financial

activities has been remarkable creating a financial asset bubble to

rival anything seen in the history of financial excesses. And together

with statistical suppression of the effect on consumer prices the switch

of economic resources from Main Street to Wall Street has hidden the

inflationary evidence of credit expansion from the public’s gaze.

All

that is coming to an end with a new commoditisation — what respected

flows analyst Zoltan Pozsar at Credit Suisse calls Bretton Woods III. In

his enumeration the first was suspended by President Nixon in 1971, and

the second ran from then until now when the dollar has ruled

indisputably. That brings us to Bretton Woods III.

Russia’s

insistence that importers of its energy pay in roubles and not in

dollars or euros is a significant development, a direct challenge to the

dollar’s role. There are no options for Russia’s “unfriendlies”,

Russia’s description for the alliance united against it. The EU, which

is the largest importer of Russian natural gas, either bites the bullet

or scrambles for insufficient alternatives. The option is to buy natural

gas and oil at reasonable rouble prices or drive prices up in euros and

still not get enough to keep their economies going and the citizens

warm and mobile. Either way, it seems Russia wins, and one way the EU

loses.

As to Pozsar’s belief that we are on the verge of Bretton

Woods III, one can see the logic of his argument. The highly inflated

financial bubble marks the end of an era, fifty years in the making.

Negative interest rates in the EU and Japan are not just an anomaly, but

the last throw of the dice for the yen and the euro. The ECB and the

Bank of Japan have bond portfolios which have wiped out their equity,

and then some. All Western central banks which have indulged in QE have

the same problem. Contrastingly, the Russian central bank and the

Peoples Bank of China have not conducted any QE and have clean balance

sheets. Rising interest rates in Western currencies are made more

certain and their height even greater by Russia’s aggressive response to

Western sanctions. It hastens the bankruptcy of the entire Western

banking system and by bursting the highly inflated financial bubble will

leave little more than hollowed-out economies.

Putin has taken as

his model the 1973 Nixon/Kissinger agreement with the Saudis to only

accept US dollars in payment for oil, and to use its dominant role in

OPEC to force other members to follow suit. As the World’s largest

energy exporter Russia now says she will only accept roubles, repeating

for the rouble the petrodollar strategy. And even Saudi Arabia is now

bending with the wind and accepting China’s renminbi for its oil,

calling symbolic time on the Nixon/Kissinger petrodollar agreement.

The

West, by which we mean America, the EU, Britain, Japan, South Korea,

and a few others have set themselves up to be the fall guys. That

statement barely describes the strategic stupidity — an Ignoble Award is

closer to the truth. By phasing out fossil fuels before they could be

replaced entirely with green energy sources, an enormous shortfall in

energy supplies has arisen. With an almost religious zeal, Germany has

been cutting out nuclear generation. And even as recently as last month

it still ruled out extending the lifespan of its nuclear facilities. The

entire G7 membership were not only unprepared for Russia turning the

tables on its members, but so far, they have yet to come up with an

adequate response.

Russia has effectively commoditised its

currency, particularly for energy, gold, and food. It is following China

down a similar path. In doing so it has undermined the dollar’s

hegemony, perhaps fatally. As the driving force behind currency values,

commodities will be the collateral replacing financial assets. It is

interesting to observe the strength in the Mexican peso against the

dollar (up 9.7% since November 2021) and the Brazilian real (up 21% over

a year) And even the South African rand has risen by 11% in the last

five months. That these flaky currencies are rising tells us that

resource backing for currencies has its attractions beyond the rouble

and renminbi.

But having turned their backs on gold, the Americans

and their Western epigones lack an adequate response. If anything, they

are likely to continue the fight for dollar hegemony rather than accept

reality. And the more America struggles to assert its authority, the

greater the likelihood of a split in the Western partnership. Europe

needs Russian energy desperately, and America does not. Europe cannot

afford to support American policy unconditionally.

That, of course, is Russia’s bet.

Russia’s point of view

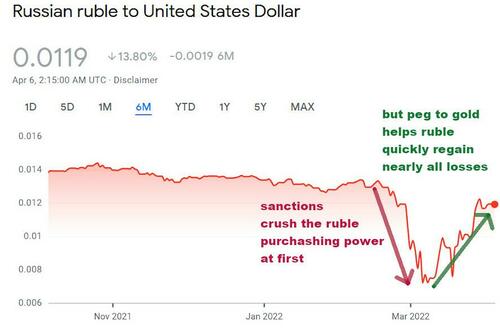

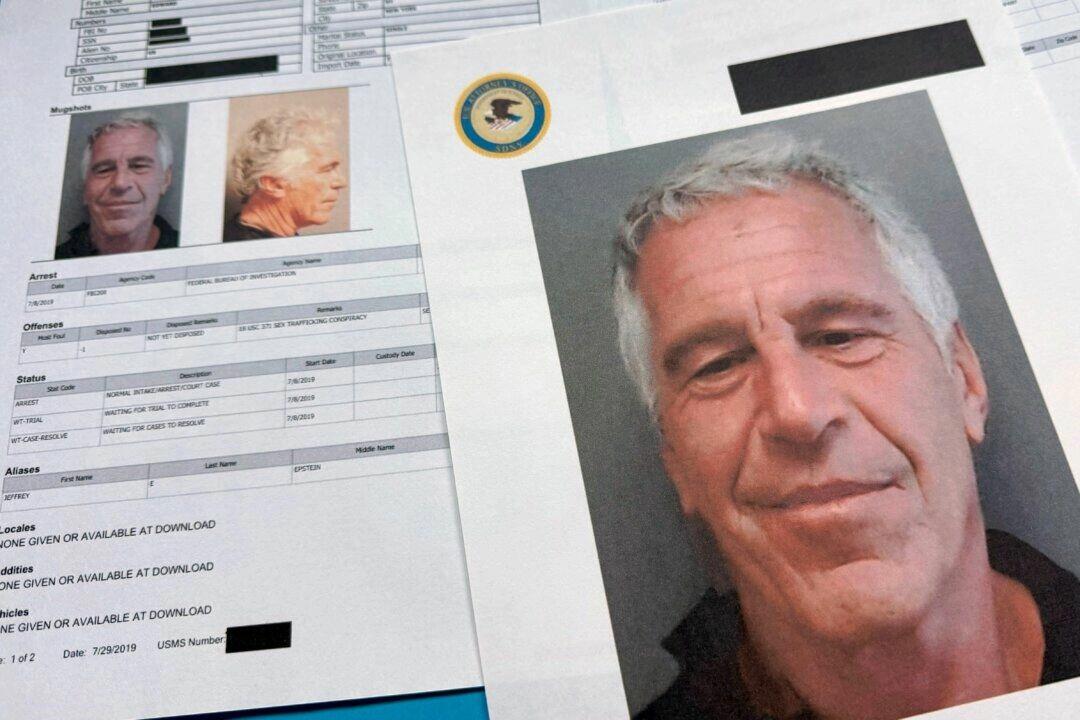

For

the second time in eight years, Russia has seen its currency undermined

by Western action over Ukraine. Having experienced it in 2014, this

time the Russian central bank was better prepared. It had diversified

out of dollars adding official gold reserves. The commercial banking

system was overhauled, and the Governor of the RCB, Elvira Nabiullina,

by following classical monetary policies instead of the Keynesianism of

her Western contempories, has contained the fall-out from the war in

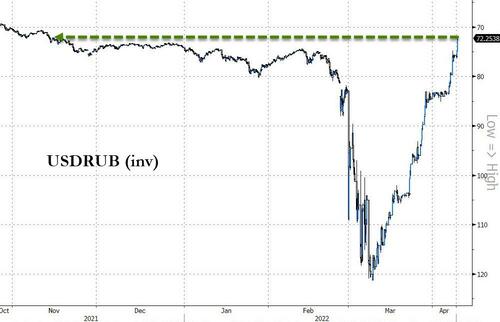

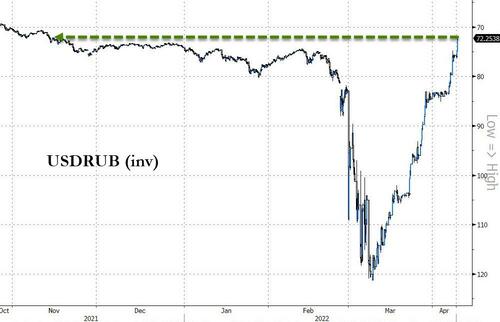

Ukraine. As Figure 1 shows, the rouble halved against the dollar in a

knee-jerk reaction before recovering to pre-war levels.

The

link to commodities is gold, and the RCB announced that until end-June

it stands ready to buy gold from Russian banks at 5,000 roubles per

gramme. The stated purpose was to allow banks to lend against mine

production, given that Russian-sourced gold is included in the

sanctions. But the move has encouraged speculation that the rouble is

going on a quasi- gold standard; never mind that a gold standard works

the other way round with users of the currency able to exchange it for

gold.

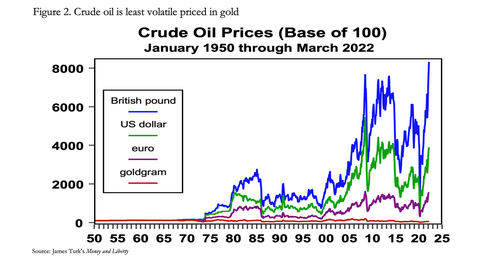

Besides being with silver the international legal definition

of money (the rest being currency and credit), gold is a good proxy for

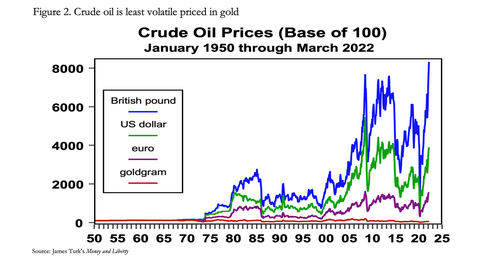

commodities, as shown in Figure 2 below. Priced in goldgrams, crude oil

today is 30% below where it was in the 1950, long before Nixon

suspended the Bretton Woods Agreement. Meanwhile, measured in

depreciating fiat currencies the price has soared and been extremely

volatile along the way.

It

is a similar story for other commodity prices, whereby maximum

stability is to be found in prices measured in goldgrams. Taking up

Pozsar’s point about currencies being increasingly linked to commodities

in Bretton Woods III, it appears that Russia intends to use gold as

proxy for commodities to stabilise the rouble. Instead of a fixed gold

exchange rate, the RCB has wisely left itself the option to periodically

revise the price it will pay for gold after 1 July.

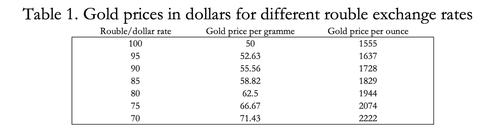

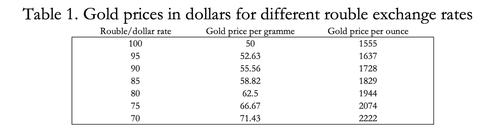

Table 1 shows how the RCB’s current fixed rouble gold exchange rate translates into US dollars.

While

non-Russian credit institutions do not have access to the facility, it

appears that there is nothing to stop a Russian bank buying gold in

another centre, such as Dubai, to sell to the Russian central bank for

roubles. All that is needed is for the dollar/rouble rate to be

favourable for the arbitrage and the ability to settle in a

non-sanctioned currency, such as renminbi, or to have access to

Eurodollars which it can exchange for Euroroubles (see below) from a

bank outside the “unfriendlies” jurisdictions.

The dollar/rouble

rate can now easily be controlled by the RCB, because how demand for

roubles in short supply is handled becomes a matter of policy. Gazprom’s

payment arm (Gazprombank) is currently excused the West’s sanctions and

EU gas and oil payments will be channelled through it.

Broadly, there are four ways in which a Western consumer can acquire roubles:

By buying roubles on the foreign exchanges.

By depositing euros, dollars, or sterling with Gazprombank and have them do the conversion as agents.

By Gazprombank increasing its balance sheet to provide credit, but collateral which is not sanctioned would be required.

By foreign banks creating rouble credits which can be paid to Gazprombank against delivery of energy supplies.

The

last of these four is certainly possible, because that is the basis of

Eurodollars, which circulate outside New York’s monetary system and have

become central to international liquidity. To understand the creation

of Eurodollars, and therefore the possibility of a developing Eurorouble

market we must delve into the world of credit creation.

There are

two ways in which foreigners can hold dollar balances. The way commonly

understood is through the correspondent banking system. Your bank, say

in Europe, will run deposit accounts with their correspondent banks in

New York (JPMorgan, Citi etc.). So, if you make a deposit in dollars,

the credit to your account will reconcile with the change in your bank’s

correspondent account in New York.

Now let us assume that you

approach your European bank for a dollar loan. If the loan is agreed, it

appears as a dollar asset on your bank’s balance sheet, which through

double-entry bookkeeping is matched by a dollar liability in favour of

you, the borrower. It cannot be otherwise and is the basis of all bank

credit creation. But note that in the creation of these balances the

American banking system is not involved in any way, which is how and why

Eurodollars circulate, being fungible with but separate in origin from

dollars in the US.

By the same method, we could see the birth and

rapid expansion of a Eurorouble market. All that’s required is for a

bank to create a loan in roubles, matched under double-entry bookkeeping

with a deposit which can be used for payments. It doesn’t matter which

currency the bank runs its balance sheet in, only that it has balance

sheet space, access to rouble liquidity and is a credible counterparty.

This

suggests that Eurozone and Japanese banks can only have limited

participation because they are already very highly leveraged. The banks

best able to run Eurorouble balances are the Americans and Chinese

because they have more conservative asset to equity ratios. Furthermore,

the large Chinese banks are majority state-owned, and already have

business and currency interests with Russia giving them a head start

with respect to rouble liquidity.

We have noticed that the large

American banks are not shy of dealing with the Chinese despite the

politics, so presumably would like the opportunity to participate in

Euroroubles. But only this week, the US Government prohibited them from

paying holders of Russia’s sovereign debt more than $600 million. So, we

should assume the US banks cannot participate which leaves the field

open to the Chinese mega-banks. And any attempt to increase sanctions on

Russia, perhaps by adding Gazprombank to the sanctioned list, achieves

nothing, definitely cuts out American banks from the action, and

enhances the financial integration between Russia and China. The gulf

between commodity-backed currencies and yesteryear’s financial fiat

simply widens.

For now, further sanctions are a matter for

speculation. But Gazprombank with the assistance of the Russian central

bank will have a key role in providing the international market for

roubles with wholesale liquidity, at least until the market acquires

depth in liquidity. In return, Gazprombank can act as a recycler of

dollars and euros gained through trade surpluses without them entering

the official reserves. Dollars, euros yen and sterling are the

unfriendlies’ currencies, so the only retentions are likely to be

renminbi and gold.

In this manner we might expect roubles, gold

and commodities to tend to rise in tandem. We can see the process by

which, as Zoltan Pozsar put it, Bretton Woods III, a global currency

regime based on commodities, can take over from Bretton Woods II, which

has been characterised by the financialisation of currencies. And it’s

not just Russia and her roubles. It’s a direction of travel shared by

China.

The economic effects of a strong currency backed by

commodities defy monetary and economic beliefs prevalent in the West.

But the consequences that flow from a stronger currency are desirable:

falling interest rates, wealth remaining in the private sector and an

escape route from the inevitable failure of Western currencies and their

capital markets. The arguments in favour of decoupling from the

dollar-dominated monetary system have suddenly become compelling.

The consequences for the West

Most

Western commentary is gung-ho for further sanctions against Russia.

Relatively few independent commentators have pointed out that by

sanctioning Russia and freezing her foreign exchange reserves, America

is destroying her own hegemony. The benefits of gold reserves have also

been pointedly made to those that have them. Furthermore, central banks

leaving their gold reserves vaulted at Western central banks exposes

them to sanctions, should a nation fall foul of America. Doubtless, the

issue is being discussed around the world and some requests for

repatriation of bullion are bound to follow.

There is also the

problem of gold leases and swaps, vital for providing liquidity in

bullion markets, but leads to false counting of reserves. This is

because under the IMF’s accounting procedures, leased and swapped gold

balances are recorded as if they were still under a central bank’s

ownership and control, despite bullion being transferred to another

party in unallocated accounts.

No one knows the extent of swaps

and leases, but it is likely to be significant, given the evidence of

gold price interventions over the last fifty years. Countries which have

been happy to earn fees and interest to cover storage costs and turn

gold bullion storage into a profitable activity (measured in fiat) are

at the margin now likely to not renew swap and lease agreements and

demand reallocation of bullion into earmarked accounts, which would

drain liquidity from bullion markets. A rising gold price will then be

bound to ensue.

Ever since the suspension of Bretton Woods in

1971, the US Government has tried to suppress gold relative to the

dollar, encouraging the growth of gold derivatives to absorb demand.

That gold has moved from $35 to $1920 today demonstrates the futility of

these policies. But emotionally at least, the US establishment is still

virulently anti-gold.

As Figure 2 above clearly shows, the link

between commodity prices and gold has endured through it all. It is this

factor that completely escapes popular analysis with every commodity

analyst assuming in their calculations a constant objective value for

the dollar and other currencies, with price subjectivity confined to the

commodity alone. The use of charts and other methods of forecasting

commodity prices assume as an iron rule that price changes in

transactions come only from fluctuations in commodity values.

The

truth behind prices measured in unbacked currencies is demonstrated by

the cost of oil priced in gold having declined about 30% since the

1960s. That is reasonable given new extraction technologies and is

consistent with prices tending to ease over time under a gold standard.

It is only in fiat currencies that prices have soared. Clearly, gold is

considerably more objective for transaction purposes than fiat

currencies, which are definitely not.

Therefore, if, as the chart

in the tweet below suggests, the dollar price of oil doubles from here,

it will only be because at the margin people prefer oil to dollars — not

because they want oil beyond their immediate needs, but because they

want dollars less.

China

recognised these dynamics following the Fed’s monetary policies of

March 2020, when it reduced its funds rate to the zero bound and

instituted QE at $120bn every month. The signal concerning the dollar’s

future debasement was clear, and China began to stockpile oil,

commodities, and food — just to get rid of dollars. This contributed to

the rise in dollar commodity prices, which commenced from that moment,

despite falling demand due to covid and supply chain problems. The

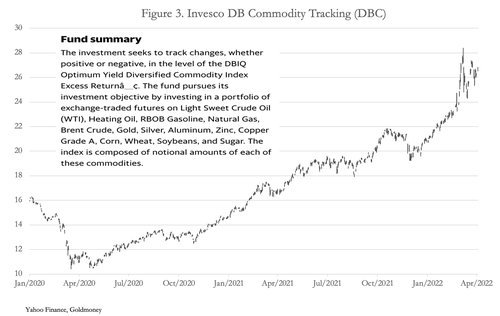

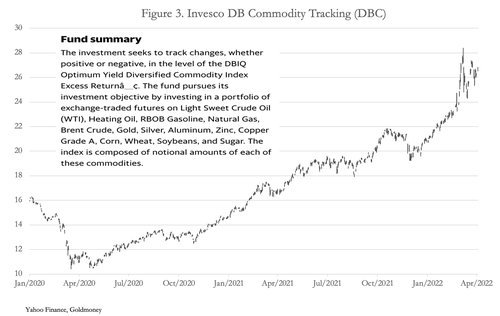

effect of dollar debasement is reflected in Figure 3, which is of a

popular commodity tracking ETF.

A

better understanding would be to regard the increase in the value of

this commodity basket not as a near doubling since March 2020, but as a

near halving of the dollar’s purchasing power with respect to it.

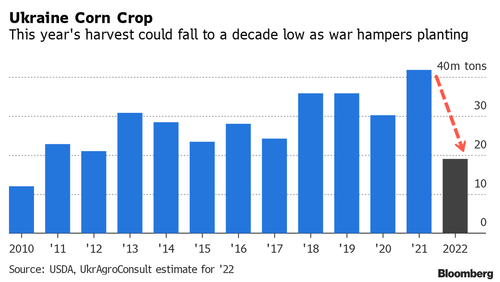

Furthermore,

the Chinese have been prescient enough to accumulate stocks of grains.

The result is that 20% of the world’s population has access to 70% of

the word’s maize stocks, 60% of rice, 50% of wheat and 35% of soybeans.

The other 80% of the world’s population will almost certainly face acute

shortages this year as exports of grain and fertiliser from

Ukraine/Russia effectively cease.

China’s actions show that she

has to a degree already tied her currency to commodities, recognising

the dollar would lose purchasing power. And this is partially reflected

in the yuan’s exchange rate against the US dollar, which since May 2020

has gained over 11%.

Implications for the dollar, euro and yen

In

this article the close relationship between gold, oil, and wider

commodities has been shown. It appears that Russia has found a way of

tying her currency not to the dollar, but to commodities through gold,

and that China has effectively been doing the same thing for two years

without the gold link. The logic is to escape the consequences of

currency and credit expansion for the dollar and other Western

currencies as their purchasing power is undermined. And the use of a

gold peg is an interesting development in this context.

We should

bear in mind that according to the US Treasury TIC system foreigners own

$33.24 trillion of financial securities and short-term assets including

bank deposits. That is in addition to a few trillion, perhaps, in

Eurodollars not recorded in the TIC statistics. These funds are only

there in such quantities because of the financialisation of Western

currencies, a situation we now expect to end. A change in the world’s

currency order towards Pozsar’s Bretton Woods III can be expected to a

substantial impact on these funds.

To prevent foreign selling of

the $6.97 trillion of short-term securities and cash, interest rates

would have to be raised not just to tackle rising consumer prices (a

Keynesian misunderstanding about the economic role of interest rates,

disproved by Gibson’s paradox) but to protect the currency on the

foreign exchanges, particularly relative to the rouble and the yuan.

Unfortunately, sufficiently high interest rates to encourage short-term

money and deposits to stay would destabilise the values of the foreign

owned $26.27 trillion in long-term securities — bonds and equities.

As

the manager of US dollar interest rates, the dilemma for the Fed is

made more acute by sanctions against Russia exposing the weakness of the

dollar’s position. The fall in its purchasing power is magnified by

soaring dollar prices for commodities, and the rise in consumer prices

will be greater and sooner as a result. It is becoming possible to argue

convincingly that interest rates for one-year dollar deposits should

soon be in double figures, rather than the three per cent or so argued

by monetary policy hawks. Whatever the numbers turn out to be, the

consequences are bound to be catastrophic for financial assets and for

the future of financially oriented currencies where financial assets are

the principal form of collateral.

It appears that Bretton Woods

II is indeed over. That being the case, America will find it virtually

impossible to retain the international capital flows which have allowed

it to finance the twin deficits — the budget and trade gaps. And as

securities’ values fall with rising interest rates, unless the US

Government takes a very sharp knife to its spending at a time of

stagnating or falling economic activity, the Fed will have to step up

with enhanced QE.

The excuse that QE stimulates the economy will

have been worn out and exposed for what it is: the debasement of the

currency as a means of hidden taxation. And the foreign capital that

manages to escape from a dollar crisis is likely to seek a home

elsewhere. But the other two major currencies in the dollar’s camp, the

euro and yen, start from an even worse position. These are shown in

Figure 4. With their purchasing power visibly collapsing the ECB and the

Bank of Japan still have negative interest rates, seemingly trapped

under the zero bound. Policy makers find themselves torn between the

Scylla of consumer price inflation and the Charybdis of declining

economic activity. A further problem is that these central banks have

become substantial investors in government and other bonds (the BOJ even

has equity ETFs on board) and rising bond yields are playing havoc with

their balance sheets, wiping out their equity requiring a systemic

recapitalisation.

Not

only are the ECB and BOJ technically bankrupt without massive capital

injections, but their commercial banking networks are hugely

overleveraged with their global systemically important banks — their

G-SIBs — having assets relative to equity averaging over twenty times.

And unlike the Brazilian real, the Mexican peso and even the South

African rand, the yen and the euro are sliding against the dollar.

The

response from the BOJ is one of desperately hanging on to current

policies. It is rigging the market by capping the yield on the 10-year

JGB at 0.25%, which is where it is now.

These currency

developments are indicative of great upheavals and an approaching

crisis. Financial bubbles are undoubtedly about to burst sinking fiat

financial values and all that sail with them. Government bonds will be

yesterday’s story because neither China nor Russia, whose currencies can

be expected to survive the transition from financial to commodity

orientation, run large budget deficits. That, indeed, will be part of

their strength.

The financial war, so long predicted and described

in my essays for Goldmoney, appears to be reaching its climax. At the

end it has boiled down to who understands money and currencies best. Led

by America, the West has ignored the legal definition of money,

substituting fiat dollars for it instead. Monetary policy lost its

anchor in realism, drifting on a sea of crackpot inflationary beliefs

instead.

But Russia and China have not made the same mistake.

China played along with the Keynesian game while it suited them.

Consequently, while Russia may be struggling militarily, unless a

miracle occurs the West seems bound to lose the financial war and we

are, indeed, transiting into Pozsar’s Bretton Woods III.